Descubren la corona y el escudo de Alejandro Magno

Arqueólogos griegos y estadounidenses descubren que la tumba que se pensaba que albergaba al padre de Alejandro Magno, es en realidad la de su medio hermano. Esto puede significar que algunos de los artefactos encontrados en la tumba, incluyendo un casco, un escudo y una corona de plata, podrían haber pertenecido originalmente al mismísimo Alejandro Magno.

Esto lo creen porque el medio hermano de Alejandro se cree que reclamó toda la parafernalia tras la muerte del conquistador.

La tumba es una de las tres tumbas reales macedonias excavadas en 1977 por arqueólogos que trabajaban en la villa Vergina, al norte de Grecia. Allí los excavadores encontraron una banda de plata para usarse en la cabeza, un casco de hierro, y un escudo ceremonial, junto con una gran cantidad de armas y un objeto identificado como un cetro.

En aquel momento lo anunciaron como la tumba de Filipo II de Macedonia, el padre de Alejandro que fue asesinado en 336 antes de Cristo. Pero análisis recientes que fueron realizados por Eugene N. Borza, de la Universidad Estatal de Pennsylvania, demostró que los restos son mucho más recientes de lo que se pensaba.

Borza cree que es de la época de Alejandro, y que los restos arqueológicos son del mismo Alejandro, si bien no es su tumba. La tumba es una caja de piedra simple, que contiene los restos no identificados de un hombre adulto, una mujer joven y un niño recién nacido. La segunda tumba, abovedada y con dos cámaras, contiene los restos de una mujer joven y de un hombre maduro. La tercera, con dos cámaras abovedadas, contenía los restos humanos de un adolescente que se cree que sería un hombre.

Las dos tumbas más grandes tienen ornamentos de oro, de plata, de marfil, así como vasos de cerámica y metal.

Borza se contactó con Olga Palagia, historiadora del arte de la Universidad de Atenas, para evaluar las cerámicas y pinturas de las tumbas. Al poco tiempo se dieron cuenta del hecho de que las tumbas 2 y 3 fueron hechas con un estilo de cielorraso curvado llamado bóvedas tipo barril. "La fecha más temprana para una bóbeda barril en Grecia data de fines del 320 antes de Cristo, casi una generación luego de la muerte de Filipo II", dijo Borza.

Palagia también descubrió que las pinturas en el friso exterior de la tumba reflejan temas que eran más típicos de la época de Alejandro Magno que de la de su padre.

El cetro de dos metros encontrado en una de las tumbas es otra pista, dice Borza. "Tenemos muchas monedas acuñadas en vida de Alejandro, que lo muestran a él sosteniendo un cetro muy parecido", agregó.

Y como si fuere poco los vasos encontrados también tienen un peso que se condice con el sistema de medidas que instauró Alejandro durante su reinado.

Una vez determinado que la tumba no es de Filipo y que es una generación posterior a su muerte, entonces ya se puede realizar la pregunta de a quién pertenece.

En los textos antiguos se pudo encontrar un doble entierro, así que pudieron identificar que la tumba pertenece a Filipo III Arrideo y a su reina Eurídice. La tercera tumba creen que puede ser de Alejandro IV, el hijo de Alejandro Magno, que reinó junto con Arrideo hasta que fue asesinado cerca del 310 antes de Cristo, ya que coincide con la edad atribuida a los restos y es el único adolescente mecedonio de la familia real que se sepa que fue enterrado.

La tumba 1 si es antigua, así que esa podría ser la de Filipo II, ya que también tiene a una mujer, su esposa, y a un niño.

Vía: National Geographic

Fuente: Martín Cagliani/EspacioCiencia.com, 24 de abril de 2008

(2) Alexander the Great's "Crown," Shield Discovered?

Sara Goudarzi

for National Geographic News

April 23, 2008

An ancient Greek tomb thought to have held the body of Alexander the Great's father is actually that of Alexander's half brother, researchers say.

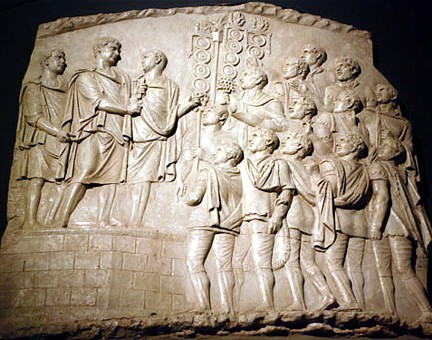

This may mean that some of the artifacts found in the tomb-including a helmet, shield, and silver "crown"-originally belonged to Alexander the Great himself. Alexander's half brother is thought to have claimed these royal trappings after Alexander's death.

The tomb was one of three royal Macedonian burials excavated in 1977 by archaeologists working in the northern Greek village of Vergina.

Excavators at the time found richly appointed graves with artifacts including a unique silver headband, an iron helmet, and a ceremonial shield, along with a panoply of weapons and an object initially identified as a scepter.

"Archaeologists announced that the burial in the main chamber of the large rich tomb was that of Philip II, father of Alexander the Great, who was assassinated in 336 B.C," said Eugene N. Borza, professor emeritus of ancient history at Pennsylvania State University.

But recent analyses of the tombs and the paintings, pottery, and other artifacts found there, suggest that the burials are in fact one generation more recent than had previously been thought, Borza said.

"Regarding the paraphernalia we attribute to Alexander, no single item constitutes proof, but the quality of the argument increases with the quantity of information," he said.

"We believe that it is likely that this material was Alexander's. As for the dating of the tombs themselves, this is virtually certain."

Tomb Mystery

The original excavation at Vergina was led by Manolis Andronikos, an archaeologist at Greece's Aristotle University of Thessaloniki who died in 1992.

His team found the first tomb to be a simple stone box containing human remains identified as a mature male, a somewhat younger female, and a newborn.

Tomb II, a large vaulted tomb with two chambers, contained the remains of a young woman and a mature male.

Tomb III, with two vaulted chambers, was the resting place of a young teenager, most likely a male.

Both of the larger tombs contained gold, silver, and ivory ornaments, as well as ceramic and metal vessels.

"Andronikos presented his theories that the tombs were those of Alexander's father and his family with great skill, and the Greek nation responded with fervent enthusiasm," Borza said.

"Indeed I was one of those who, in two early articles in the late 1970s, accepted Andronikos' view that the remains were those of Philip II."

Borza started to doubt Andronikos' conclusions, however, as he studied the evidence.

He contacted Olga Palagia, an art historian at the University of Athens, to evaluate the tombs' construction, pottery, and paintings.

Soon the duo realized the significance of the fact that Tomb II and Tomb III were built using a curved ceilings called barrel vaults.

"The earliest securely dated barrel vault in Greece dates to the late 320s [B.C.], nearly a generation after the death of Philip II," Borza told National Geographic News.

Palagia also found that paintings on the exterior frieze of the tomb reflected themes that were likely from the age of Alexander the Great, rather than that of his father.

The paintings depict a ritual hunt scene with Asian themes, suggesting influences resulting from Alexander's extensive campaigns to the east.

Treasures

The six-foot (two-meter) scepter found at the burial site is another clue, Borza added.

"We have several surviving coins issued in his own lifetime showing Alexander holding what appears to be a scepter of about that height," he said.

Additionally, a number of silver vessels discovered in Tomb II and Tomb III are inscribed with their ancient weights, which use a measurement system introduced by Alexander the Great a generation after Philip II's death.

"Once we have determined on archaeological grounds that Tomb II is a generation later than Philip II's death, we can then ask, Whose tomb is it?" Borza said.

"We have a double royal burial from this era attested in the ancient literature. Thus the tomb is that of Alexander's half brother Philip III Arrhidaeus and his queen, Adea Eurydice."

Borza and Palagia discussed their new analysis at the meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America in January. Their findings will be published in a forthcoming study from the German Archaeological Institute.

Most of the ancient artifacts found at Vergina are on display today at a museum at the site of the tombs.

Death of Alexander

Alexander died of disease in ancient Babylon, near modern-day Baghdad, Iraq, in 323 B.C.

His generals appointed Philip III to take his place, and the half brother claimed Alexander's royal objects as public symbols to solidify his power, historians suggest.

Alexander's son, Alexander IV, who was appointed joint king along with Philip III, was assassinated around 310 B.C. He is likely buried in Vergina's Tomb III, which contains the remains of a young teenager, Borza said.

Historically, the only known Macedonian royal teenage burial is that of Alexander IV, he explained.

Alexander's father, Phillip II, is buried in Tomb I, along with his wife and their infant, according to Borza.

"Tomb I is from the age of Philip II-unlike the big chamber tombs, which are later-and the human remains of the three burials accord well with the assassinations of these individuals."

Winthrop Lindsay Adams, a professor of history at the University of Utah who was not involved with the study, said Borza's work builds on what other specialists have thought about the various aspects of the Vergina tombs.

The work of Borza and his colleagues convincingly make the case that Tomb II is the final resting place of Alexander's half brother, Adams explained.

"Indeed for most scholars working in fourth-century Macedonia, the original attribution by Andronikos now seems doubtful," he said. "This case is convincing."

© 1996-2008 National Geographic Society. All rights reserved.