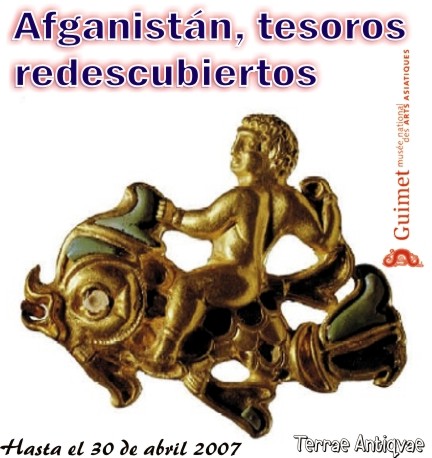

El museo Guimet de París expone las riquezas arqueológicas salvadas de la rapiña soviética y la ira talibán.

En 1978, un año antes de la invasión soviética de Afganistán, el arqueólogo Viktor Sarianidi descubre por casualidad en la frontera norte del país un esqueleto femenino recubierto con objetos de oro. Las excavaciones dirigidas por este científico, oriundo de Uzbekistán, permiten exhumar otras cinco tumbas intactas de príncipes nómadas que vivieron en el siglo I de nuestra era. Las piezas más rutilantes de este extraordinario tesoro, salvado de la rapiña soviética y la ira iconoclasta talibán, son exhibidas por primera vez al público en París por el Museo de Artes Asiáticas Guimet en una exposición programada hasta el 30 de abril.

La historia de la necrópolis de Tillia-Tepe (Colina de Oro), último gran hallazgo arqueológico antes de que Afganistán cayera en el caos, es digna de una novela de aventuras. En 1979, ante la degradación del clima político, el tesoro formado por 21.618 piezas de las que 20.478 son de oro fue trasladado bajo escolta militar hasta el museo de Kabul donde permaneció una decena de años.

En 1988, con el país al borde de la guerra civil entre comunistas y rebeldes, el presidente prosoviético Mohamed Najibulá ordenó encerrar las piezas más valiosas en una caja fuerte del Banco Central, en los sótanos del antiguo palacio real de Arg. Para reforzar la seguridad confió las siete llaves que abrían la puerta de la cámara acorazada a siete personas diferentes, conforme a la tradición afgana.

Los comunistas, primero, y luego los talibanes intentaron en vano forzar los cerrojos de los cofres pero no pudieron impedir la propagación de todo tipo de rumores. Se creía que el tesoro bajo siete llaves había sido robado y transportado a lomo de mula hasta las cavernas de Panchir para negociarlo con mayor libertad. Se pensó que Bin Laden lo había sacado del país para financiar Al Qaeda con el producto de la venta. Y muchos estaban convencidos de que había seguido el camino del oro de Moscú y llevaba tiempo escondido en el Kremlin.

En 2002, tras el derrocamiento del régimen talibán, se comenzó a a rumorear que las colecciones del museo de Kabul no habían sido totalmente saqueadas o expoliadas en los pillajes de los años noventa. En 2003 el presidente Amir Karzai, entonces jefe del Gobierno interino instalado por una coalición occidental, localizó las siete llaves meses después de llegar al poder. En junio de 2004 tuvo lugar la reapertura solemne de los cofres y arrancó el inventario de las obras recobradas, así como la restauración de las deterioradas por tanto trajín.

En París, el tesoro de la Colina de Oro se expone junto a frutos procedentes de otros tres yacimientos -Fullol, Ai-Khanoum y Begram- que abarcan vestigios desde el siglo IV antes de nuestra era hasta el siglo III. Completan una selección de 220 coronas, brazaletes, pendientes, platos, jarrones, estatuillas, bajorrelieves, anillos y otras piezas diversas que testimonian las múltiples influencias culturales (iraníes, indias, escitas, chinas y helenísticas) de la riqueza patrimonial de un país fecundado por la aportación de las grandes civilizaciones, en la encrucijada del Asia central con las rutas de la seda y las estepas. Una parte de los siete euros que cuesta la entrada se destina a financiar las obras de reconstrucción del museo de Kabul.

PROGRAMA

Exposición: Afganistán, tesoros redescubiertos.

Dónde: Museo Guimet de Artes Asiáticas, en París.

Cuándo: Hasta el 30 de abril.

Contenido: 200 piezas, entre la Edad de Bronce y el imperio Kushan.

Abierto: Todos los días, menos los martes.

Entrada: 7 euros.

Fuente: FERNANDO ITURRIBARRÍA, París / El Correo Digital, 5 de febrero de 2007

Enlace: http://www.elcorreodigital.com/vizcaya/

prensa/20070205/sociedad/joyas-kabul_20070205.html

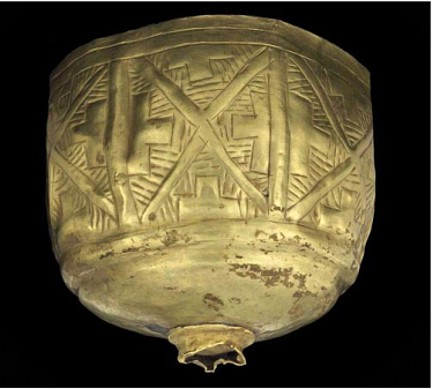

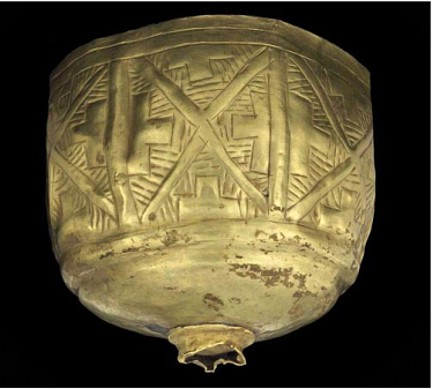

Coupe à motifs géométriques, or, Afghanistan, Tepe Fullol, Age du Bronze, fin du troisième millénaire (2100-2000 av JC). © Crédit: musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

Bol avec sanglier et décor darbre sur une montagne, or, Afghanistan, Tepe Fullol, Age du Bronze, fin du troisième millénaire (2100-2000 av JC). © Crédit: musée Guimet, archives photographiques.

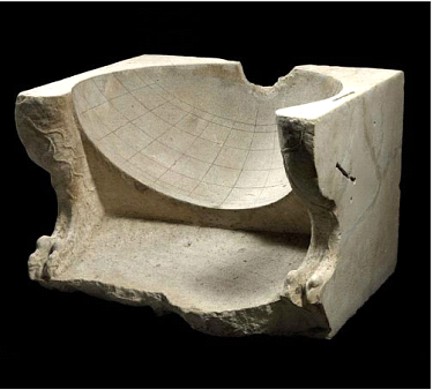

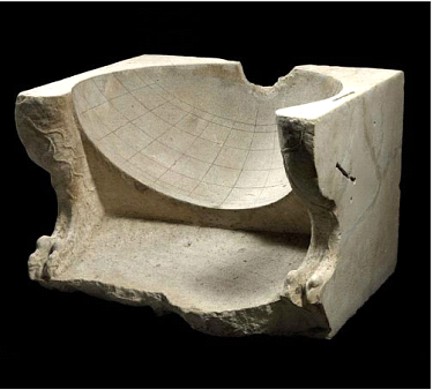

Bol à décor de taureaux barbus, or, Afghanistan, Tepe Fullol, Age du Bronze, fin du troisième millénaire (2100-2000 av JC). © Crédit: musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier. Grâce à ce cadran solaire, les habitants dAï Khanoum avaient une idée approximative de lheure.

Cadran solaire en portion dhémisphère, Afghanistan, Aï Khanoum, Gymnase, 3ème siècle avant JC, Calcaire, Musée national de Kaboul. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

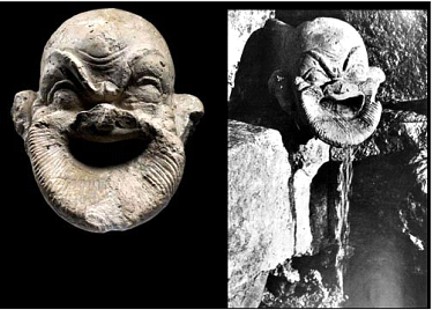

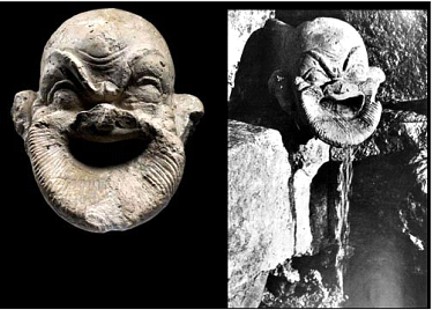

Fontaine des bords de lOxus, gargouille au masque comique, fouilles de 1975 dirigées par Paul Bernard. © musée Guimet, archives photographiques. Ce médaillon allie les imageries grecques et orientales: on y voit Cybèle, la déesse orientale de la nature debout sur un char tiré par des lions. Au-dessus delle figure Helios, le Dieu grec du soleil!

Plaque de Cybèle, Afghanistan, Aï Khanoum, sanctuaire du temple à niches indentées, 3ème s Av JC, argent doré, Musée National de Kaboul. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier.

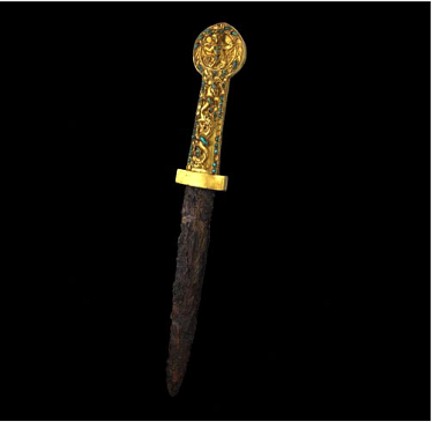

Fourreau orné dune scène de combat danimaux, Afghanistan, Tillia Tepe, or, turquoise, bois et cuir, 1er siècle, musée national de Kabou. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

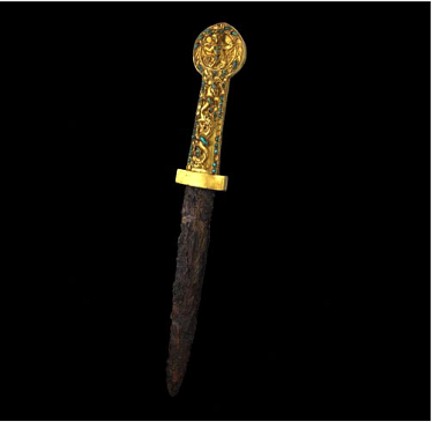

Poignard orné dune scène de combat danimaux, Afghanistan, Tillia Tepe, or, fer, turquoise, 1er siècle, musée national de Kaboul. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

Ceinture en or, Afghanistan, Tillia Tepe, 1er siècle, musée national de Kaboul. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

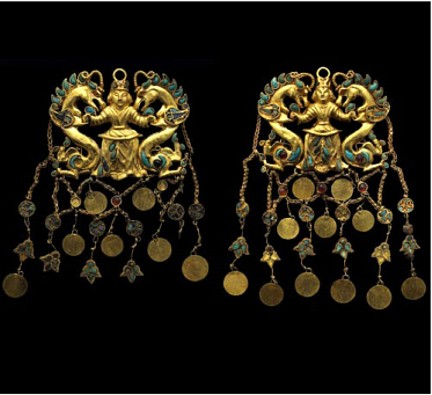

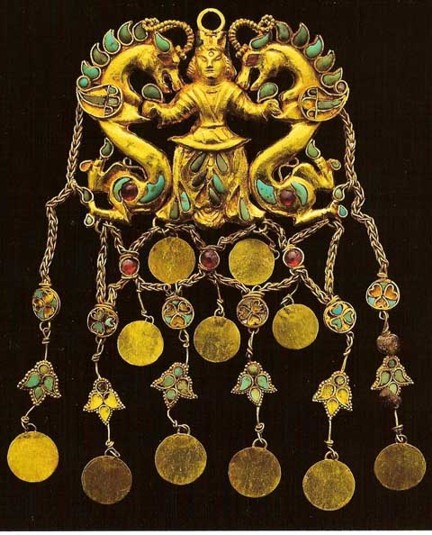

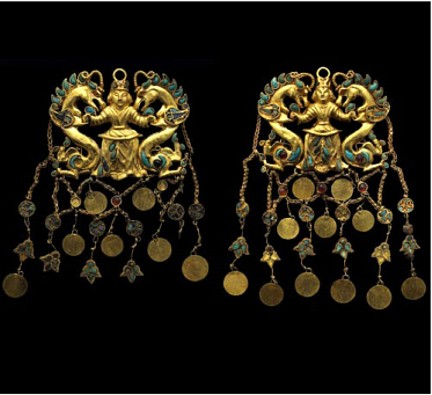

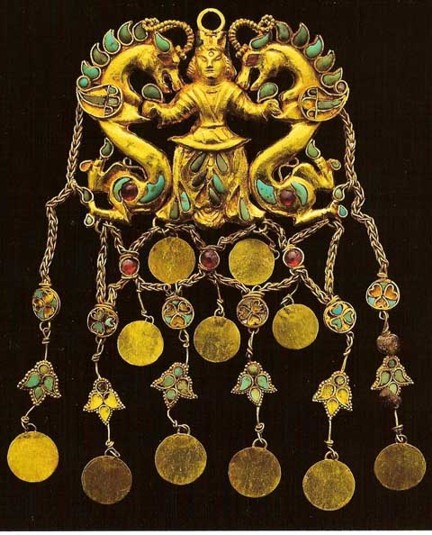

Pendeloques dîtes du "souverain et des dragons", Afghanistan, Tillia Tepe, 1er siècle, or, turquoise, grenats, lapis-lazuli, musée national de Kaboul.

© musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

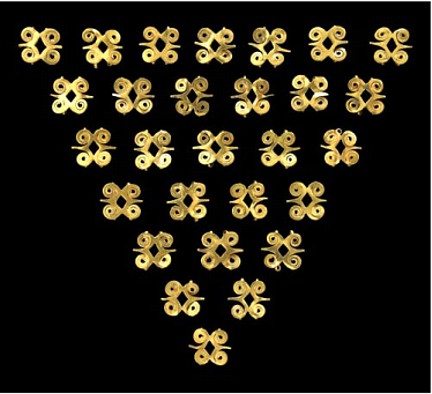

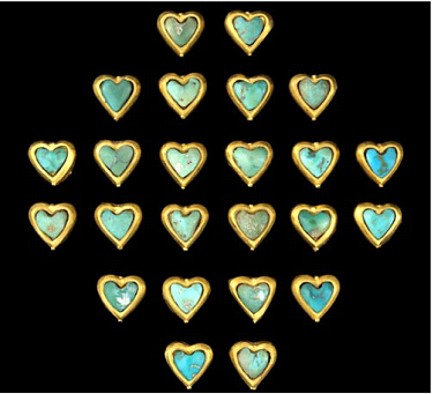

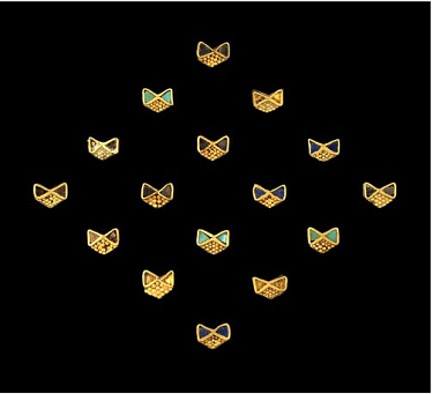

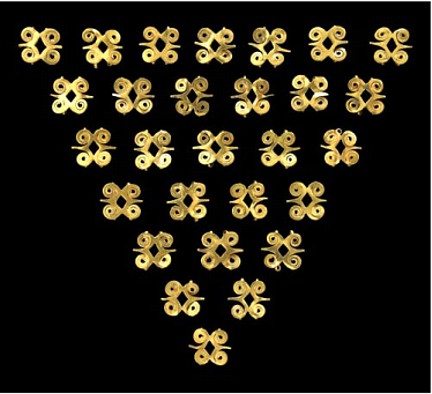

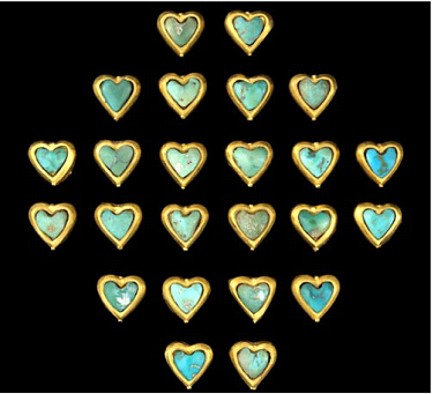

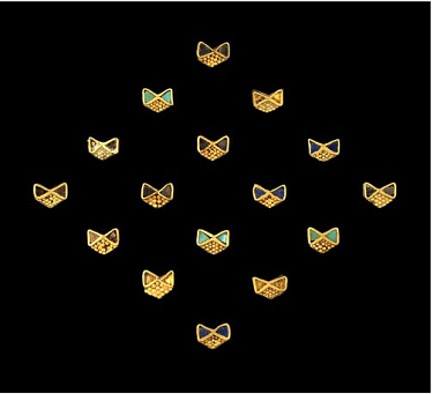

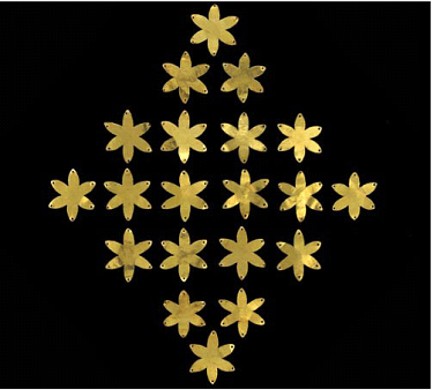

Plaquettes, Afghanistan, Tillia Tepe, or, turquoise, cornaline, grenats, 1er siècle, musée national de Kaboul. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

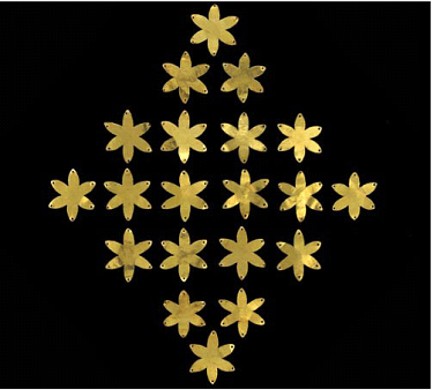

Plaquettes, Afghanistan, Tillia Tepe, or, turquoise, cornaline, grenats, 1er siècle, musée national de Kaboul. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

Plaquettes, Afghanistan, Tillia Tepe, or, turquoise, cornaline, grenats, 1er siècle, musée national de Kaboul. © Crédit : musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

Plaquettes, Afghanistan, Tillia Tepe, or, turquoise, cornaline, grenats, 1er siècle, musée national de Kaboul © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

Plaquettes, Afghanistan, Tillia Tepe, or, turquoise, cornaline, grenats, 1er siècle, musée national de Kaboul. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

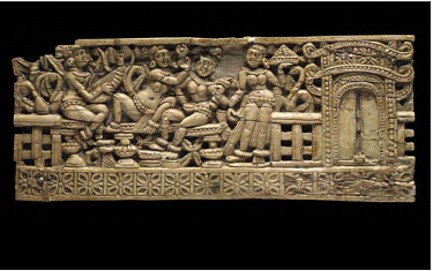

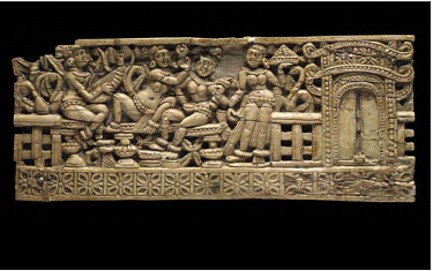

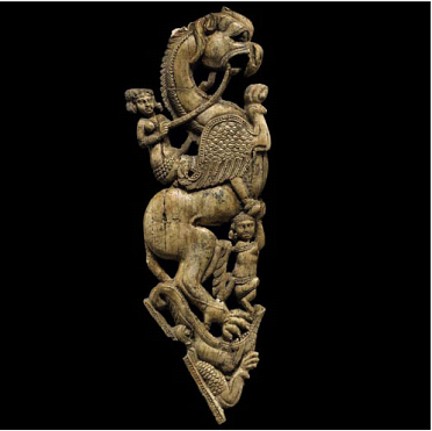

Scène de palais, trésor de Bégram, Ivoire. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

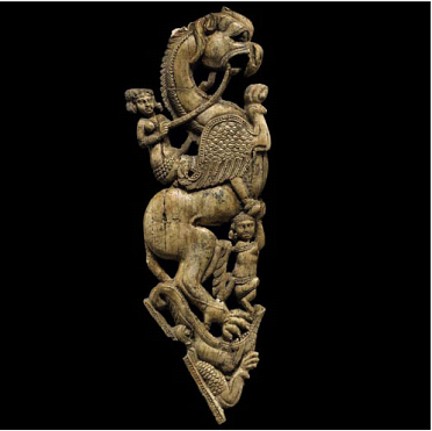

Quel étrange objet! Tu distingues peut-être tout en bas le fantastique makara qui crache une cavalière à dos de léogryphe.

Cavalière chevauchant un léogryphe, trésor de Bégram, Ivoire. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

Flacon ichthyomorphe, Trésor de Begram, verre soufflé. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

En bas, le monde de la mer : poissons, coquillages et pêcheur. En haut, la terre ferme : un tigre à la poursuite dun bouquetin!

Grand gobelet à décor peint, scène de chasse et de pêche, Trésor de Bégram, verre incolore. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

Feuille de lierre dans les cheveux, longue barbe et nez épaté, voici Silène, le dieu grec de livresse.

Masque de Silène, trésor de Begram, bronze. © musée Guimet, Thierry Ollivier

Cet objet fait partie des curiosités du trésor de Begram. Cest un aquarium en bronze, où de petits poissons métalliques, suspendus par des chainettes semblent flotter une fois le bassin rempli deau.

Fotos: © Musée des arts asiatiques - Guimet

(2) Alexanders Afghan gold

After establishing the Egyptian port city of Alexandria in 331 BC, Alexander the Great founded Greek garrison cities across Asia, including Afghanistan. His legacy is on show in a new Paris exhibition, writes David Tresilian

"Sovereign and Dragon" pendant found at the Tillia Tepe treasure

Alexander the Great, detail from a mosaic dated to the late second century BC

A ring with the image of Athena, part of the Tillia Tepe treasure

While not drawing quite the crowds making their way to the Grand Palais for Trésors engloutis dEgypte, an exhibition of mostly Ptolemaic artefacts -- "submerged treasures" -- discovered off the coast of Alexandria and reviewed in Al-Ahram Weekly on 14 December, Afghanistan, les trésors retrouvés across Paris at the Musée Guimet should nevertheless be on the itinerary of every visitor to the French capital.

This exhibition features discoveries of international importance made by French archaeological missions in Afghanistan over the course of the last century, most of which have never been seen before outside the country. In what is being seen as quite a coup both for the Musée Guimet, an institution specialising in south and south-east Asian art, and for the French capital, the exhibition allows visitors to gain their first glimpses of material that not only has never been lent before by the Afghan National Museum in Kabul, but that was also considered lost during the decade of civil war that wracked Afghanistan following the withdrawal of Soviet forces in 1989, destroying much of the country as it did so.

The material includes the famous "Bactrian gold" discovered by joint French and Afghan archaeologists in northern Afghanistan shortly before Soviet forces moved into the country in 1979. This material, long thought lost, survived the later civil war locked in the vaults of the National Bank in Kabul, where it was "rediscovered" following the US-led invasion in October 2001. It also includes Hellenistic objects from excavations carried out at the site of the ancient city of Ai Khanoum north of Kabul and Hellenistic and Indian materials found at Begram (Bagram).

Taken as a whole, Afghanistan, les trésors retrouvés is one of the most important archaeological exhibitions to have visited the French capital for years, and it is the only opportunity European and international visitors will have to view this material before it moves onto the US leg of its world tour in April 2007. It is a fine successor to Afghanistan, une histoire millénaire (Afghanistan: A Timeless History), an exhibition of mostly Graeco-Buddhist Afghan materials brought together in the wake of the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban, also at the Musée Guimet and reviewed in the Weekly in March 2002.

The exhibition is divided into three parts, the first of which displays materials discovered at Ai Khanoum by successive French archaeological missions, providing insights into the functioning of this Hellenistic garrison city founded following Alexander the Greats conquest of the area in the late fourth century BC. Alexanders epic journeys took him from his native Macedonia in northern Greece to the plains of the western Punjab in what is now Pakistan, destroying the Persian Empire as he did so, as well as through Anatolia, the Levant and to Egypt, where he founded the port city of Alexandria and consulted the oracle of Amun at Siwa.

Following Alexanders death in 323, his generals divided his conquests among themselves, Ptolemy taking Egypt and turning it into the richest and longest-lasting Hellenistic kingdom, and Seleucus taking the vast territories Alexander had conquered in Asia and controlling Greek garrison cities almost to the Indus River. Ai Khanoum was one of these, and the present exhibition includes notable items discovered at the site, as well as a rewarding Japanese video reconstruction of how the city might once have looked.

Visitors to the Musée Guimets earlier Afghan exhibition in 2002 will be aware of the heartbreaking damage done to the excavated materials and to this site itself during Afghanistans period of civil war and Taliban rule, photographs in the catalogue showing excavated Hellenistic mosaics churned up and destroyed and Greek building capitals re-used to support wooden posts in village tea-houses.

While the international protests that came in the wake of Taliban threats to destroy the monumental statues of the Buddha at Bamiyan in southern Afghanistan in the event did nothing to save these fourth-century-AD statues, they at least drew attention to the unique form of art pioneered in this region. Hellenistic culture in south Asia gradually gave way to Buddhism, itself in turn later replaced by Islam, but as it did so Greek sculptural forms gave shape to figures from the new religion. This resulted not only in the colossal representations of the Buddha at Bamiyan but also in the many sculptures of bodhisattvas, monks and ascetics that have been found at the sites of Buddhist monasteries in Afghanistan, notably at Hadda near Jalalabad in the south-east of the country, and at the Gandhara Buddhist sites in neighbouring Pakistan.

The collections of such materials once held by the Afghan National Museum have been destroyed. However material shipped to France under find-sharing arrangements can still be seen upstairs at the Musée Guimet, including the so- called Génie aux fleurs, an Afghan Hellenistic statue acquired by André Malraux in the 1920s. For the present writer, one of the highlights of any trip to Pakistan has to be a visit to the archaeological museum in Peshawar near the Afghan border, which contains one of the worlds finest collections of this kind of Buddhist art.

As far as the present exhibition is concerned, for many visitors the highlight will be the "Bactrian Gold" found in 1978 at the archaeological site of Tillia Tepe ("mound of gold") in northern Afghanistan and displayed in the shows second room. Dating from the first century AD, this includes brooches, rings, earrings and decorative hair pieces made of gold and lapis lazuli, and was found in six tombs, five of women and one of a man. Together, these items testify to the role Afghanistan has played for millennia as the gateway to India and to south and east Asia. The tombs contain Hellenistic items such as rings and other objects bearing the image of the goddess Athena, as well as items bearing the stamp of Indian and Chinese cultures, showing how different cultural influences came together in this region in the centuries following Alexanders conquest.

The exhibitions third and final room contains objects found walled up in two underground chambers at Begram by French archaeological missions in 1937, again including objects coming from the Greek Mediterranean world and from India and China. In addition to numerous Indian ivories, the chambers contained items testifying to the memory at least of Hellenistic culture.

There are plaster medallions representing Zeus and Ganymede, as well as the youth Endymion, condemned to eternal sleep to preserve his beauty. Bronze statuettes represent Eros and Harpocrates and, most intriguingly of all, fragments of a painted glass vessel show Homers story of the combat between Achilles and Hector at Troy. Unlike the gold items found at Tillia Tepe, the Begram hoard has no great value, aside from the information it contains regarding the history and culture of this area in late antiquity.

In the publicity material accompanying the exhibition, Jean-François Jarrige, president of the Musée Guimet, explains the personal interest taken in the show by both Hamid Karzai, president of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, and by the French president, Jacques Chirac. The choice of Paris for this exhibition "was not unconnected" with the decision taken by the Afghan king Amanullah in the early 20th century to confer the countrys educational system and archaeological sites to the French, Jarrige says, perhaps a calculated gesture in the direction of the British regime that then ruled much of neighbouring India.

Whatever the case may be, visitors to Afghanistan, les trésors retrouvés have reason to be grateful to the generations of French and Afghan archaeologists who have worked so tirelessly to recover the areas history, latterly under very difficult circumstances. The result here, in the words of Jarrige, is an exhibition that moves the visitor by "works of exceptional quality that speak to us of Alexander the Great, of Egypt and of the Hellenistic Near East, of Indo-Greek kings, of aristocrats of the steppes, and of the Roman, Parthian, Indian and Chinese empires."

Afghanistan, les trésors retrouvés, Musée Guimet, Paris, 6 December 2006--30 April 2007.

Source Link: http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2007/830/he1.htm

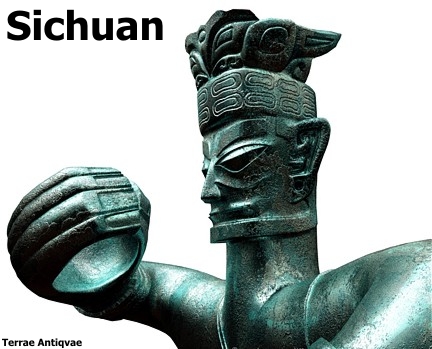

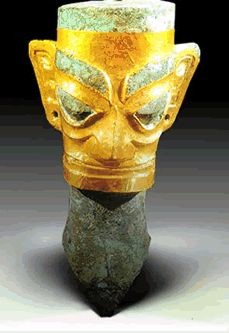

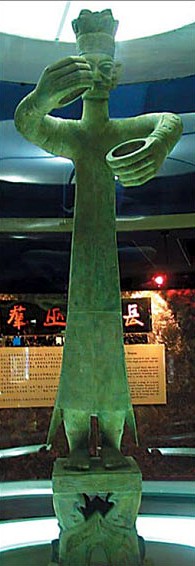

Días después llegaron los especialistas desde la capital provincial, Chengdú (Sanxingdui queda a unos cuarenta kilómetros al noreste de Chengdú), y encontraron unas extrañas máscaras de bronce. Una de ellas estaba recubierta de oro, pero el arqueólogo jefe engañó a los aldeanos, diciéndoles que no era oro, sino bronce pintado, para no excitar su interés. Echó tierra al asunto y se fue inmediatamente a Chengdú a buscar a la policía y dar la señal de alarma. No se sabía qué era aquello, pero era importante y valioso.

Días después llegaron los especialistas desde la capital provincial, Chengdú (Sanxingdui queda a unos cuarenta kilómetros al noreste de Chengdú), y encontraron unas extrañas máscaras de bronce. Una de ellas estaba recubierta de oro, pero el arqueólogo jefe engañó a los aldeanos, diciéndoles que no era oro, sino bronce pintado, para no excitar su interés. Echó tierra al asunto y se fue inmediatamente a Chengdú a buscar a la policía y dar la señal de alarma. No se sabía qué era aquello, pero era importante y valioso.

La historia se repetía. Trece años antes, en 1974, otro grupo de campesinos había encontrado estatuas de terracota cuando cavaba un pozo cerca de Xian: el ejército de terracota de Shihuangdi, considerado el "primer emperador" de China. La gran tumba imperial corroboraba la ortodoxia histórica china que localiza el origen de su milenaria civilización en el curso medio-bajo del Río Amarillo.

La historia se repetía. Trece años antes, en 1974, otro grupo de campesinos había encontrado estatuas de terracota cuando cavaba un pozo cerca de Xian: el ejército de terracota de Shihuangdi, considerado el "primer emperador" de China. La gran tumba imperial corroboraba la ortodoxia histórica china que localiza el origen de su milenaria civilización en el curso medio-bajo del Río Amarillo.  Antes de 1986, ya se habían encontrado restos en Sanxingdui. En 1929 un campesino llamado Yan Daocheng ya había encontrado allí un disco de jade mientras cavaba junto a su casa y desde entonces se realizaron diversas excavaciones e incluso alguna foto aérea, pero lo encontrado no se consideraba muy antiguo y, como mucho, se atribuía a la dinastía Han (206 a.C.-202 d.C.).

Antes de 1986, ya se habían encontrado restos en Sanxingdui. En 1929 un campesino llamado Yan Daocheng ya había encontrado allí un disco de jade mientras cavaba junto a su casa y desde entonces se realizaron diversas excavaciones e incluso alguna foto aérea, pero lo encontrado no se consideraba muy antiguo y, como mucho, se atribuía a la dinastía Han (206 a.C.-202 d.C.).

La 'Crónica de Huayang'

La 'Crónica de Huayang'

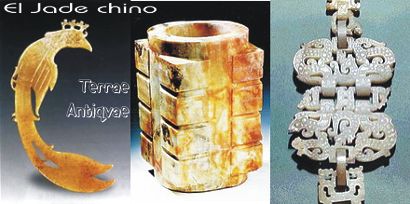

El jade se encuentra en las montañas y en los lechos de los ríos. Desde tiempos remotos, los chinos lo han considerado «la esencia del Cielo y la Tierra ». En cuanto a las diferentes formas que adopta una vez pulido y tallado, estas vienen dictadas por la tradición.

El jade se encuentra en las montañas y en los lechos de los ríos. Desde tiempos remotos, los chinos lo han considerado «la esencia del Cielo y la Tierra ». En cuanto a las diferentes formas que adopta una vez pulido y tallado, estas vienen dictadas por la tradición.