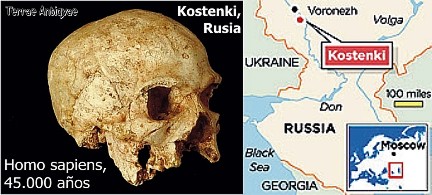

Un estudio indica que los seres humanos modernos llegaron a Europa hace 45.000 años

Photo: State University of New York at Stony Brook. Scientists used radiation absorbed by sand in this skull to find its age.

La primera presencia se ha detectado en Kostenski, al sur de Moscú

El homo sapiens era más desarrollado que los neandertales de la época. Descubren huesos y herramientas de marfil a orillas del río Don.

Los seres humanos modernos llegaron hace 45 mil años al este de Europa procedentes de África, según un estudio que hoy publica la revista Science.

John Hoffecker, paleontólogo de la Universidad de Colorado, asegura que la primera presencia del hombre moderno en Europa fue detectada en la zona de Kostenski, en una capa de cenizas volcánicas en el río Don, a unos 400 kilómetros al sur de Moscú.

Se trataría de uno de los primeros lugares colonizados por el hombre africano en Europa, según explicó Hoffecker en una entrevista telefónica.

Se cree que los seres humanos modernos aparecieron en África, al sur del Sahara, hace 200 mil años.

Queremos ser muy cautelosos al afirmarlo. Sabemos que hay otros yacimientos arqueológicos de hace poco más de 40 mil años en Bulgaria o en Italia. Pero estamos muy seguros de los datos sobre la antigüedad de Kostenski, indicó.

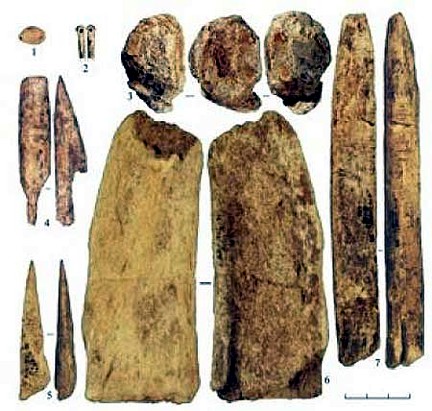

Hoffecker, que encabezó el grupo en el que también participaron los científicos rusos Mijail Anikovich y Andrey Sinitsyn, de la Academia Rusa de Ciencias, aseguró que en el lugar encontraron piedras, huesos y herramientas de marfil.

También hallaron ornamentos hechos con conchas de moluscos así como una pieza tallada de marfil de un mamut que parece ser una figura humana y que representaría la primera muestra de arte figurativo del mundo, señaló.

Según el científico, lo más sorprendente del descubrimiento es que esos hombres procedentes de lo que posiblemente eran zonas tropicales de África se hayan establecido en uno de los lugares más fríos y áridos de Europa.

Este es uno de los últimos sitios que hubiéramos esperado que ocuparan hombres africanos, añadió.

Indicó que es posible que hayan colonizado ese lugar debido a que no habían llegado a él los neandertales que fueron los primeros pobladores de Europa.

A diferencia de los neandertales, estos africanos eran mucho más desarrollados. Tenían la capacidad de crear nuevas tecnologías para afrontar el frío clima y la escasez de alimentos, dijo Hoffecker.

Los neandertales, que ocuparon Europa durante más de 200 mil años parecen haber abierto la puerta del continente a estos africanos, aseguró.

Además de Kostenski, las excavaciones arqueológicas se realizaron en más de 20 sitios a lo largo del río, los cuales estaban bajo estudio desde hace muchas décadas.

Según el científico, en Kostenski se habían hallado antes artefactos y huesos de seres humanos modernos de hace entre 30 mil y 40 mil años, incluyendo agujas de marfil.

Estas indicaban que los primeros habitantes modernos de Europa ya sabían cómo trabajar las pieles de animales para ayudarles a sobrevivir las inclemencias del tiempo.

También ampliaron su dieta para incluir pequeños mamíferos o verduras en lo que constituye una forma de reinventarse tecnológicamente.

También es posible que hayan usado trampas para cazar liebres y zorros árticos explotando grandes zonas de ese hábitat con escaso desgaste de energías, añadió.

Según el estudio, gran parte de las piedras usadas para crear los artefactos encontrados en el lugar habían sido traídas desde lugares a entre 90 y 150 kilómetros de distancia.

Los moluscos perforados para los ornamentos descubiertos en los niveles inferiores del yacimiento arqueológico fueron trasladados desde el Mar Negro, a casi 500 kilómetros, según el informe.

Aunque los restos humanos recogidos en los primeros niveles de la excavación se limitan a algunos dientes, que son difíciles de asignar a algún tipo humano específico, estos artefactos son, sin lugar a duda, el trabajo de seres humanos modernos, señaló Hoffecker.

El informe indicó que la antigüedad de los sedimentos sobre la capa superior que cubría los artefactos fue establecida mediante diversos métodos.

Uno de ellos fue el análisis de un depósito de cenizas procedentes de una tremenda erupción volcánica registrada en Italia hace 40 mil años.

Locación inesperada

Los científicos estiman que el hombre moderno vio la luz en el África subsahariana hace unos 200 mil años, por lo que se sorprendieron de encontrar huellas de su presencia en Kostenki, una de las regiones más frías y secas del continente europeo.

Entre los objetos descubiertos figuran las más antiguas agujas de marfil, prueba de que los primeros europeos cosían la piel de animales para sobrevivir en el frío.

Otros indicios descubiertos en Kostenski habían revelado que los homo sapiens ampliaron rápido su régimen alimenticio para incluir pequeños mamíferos (liebres, zorros), peces de agua dulce y aves acuáticas.

Fuente: Orlando Lizama / EFE, Washington. 11 de enero de 2007

Enlace: http://www.milenio.com/tampico/milenio/nota.asp?id=455671

(2) Skull Supports Theory of Human Migration

By JOHN NOBLE WILFORD, January 12, 2007

From a new analysis of a human skull discovered in South Africa more than 50 years ago, scientists say they have obtained the first fossil evidence establishing the relatively recent time for the dispersal of modern Homo sapiens out of Africa.

Scientists used radiation absorbed by sand in this skull to find its age.

The migrants appeared to have arrived at their new homes in Asia and Europe with the distinct and unmodified heads of Africans.

An international team of researchers reported yesterday that the age of the South African skull, which they dated at about 36,000 years old, coincided with the age of the skulls of humans then living in Europe and the far eastern parts of Asia, even Australia. The skull also closely resembled skulls of those humans.

The timing, the scientists and other experts said, introduced independent evidence supporting archaeological finds and recent genetic studies showing that modern humans left sub-Saharan Africa for Eurasia between 65,000 and 25,000 years ago; probably closer to 45,000 to 35,000 years ago for Europe.

Until now, however, paleontologists had been frustrated by the absence of fossils to test the hypothesis of most geneticists that the people of sub-Saharan Africa and in Eurasia at that time were one and the same modern humans. The human fossil record in Africa from 70,000 to 15,000 years ago had been virtually blank.

Some scientists, on the other hand, have contended that the migration could have begun as early as 100,000 years ago and that in the intervening time, contact with more archaic populations like the Neanderthals could have produced recognizable changes in what became the modern humans of Eurasia. But no scientists in the migration debate have disputed that ancestors of the human species originated in Africa.

In a report in todays issue of the journal Science, a research team led by Frederick E. Grine of the State University of New York at Stony Brook concluded that the South African skull provided critical corroboration of the archaeological and genetic evidence indicating that humans in fully modern form originated in sub-Saharan Africa and migrated, almost unchanged, to populate Europe and Asia.

Dr. Grine and his colleagues said in an announcement by Stony Brook that the skull was the first fossil evidence in agreement with the out-of-Africa theory, which predicts that humans like those that inhabited Eurasia should be found in sub-Saharan Africa around 36,000 years ago.

Ted Goebel, an anthropologist at Texas A&M University who was not connected to the research, said the skull opened the way to important insights about the missing years of modern humans.

Writing in an accompanying commentary in the journal, Dr. Goebel said, Here is the first skull of an adult modern human from sub-Saharan Africa that dates to the critical period, and one that can speak to the relationship of early moderns from Africa and Europe.

The new findings pivoted on fixing the skulls age. When it was uncovered in 1952 near the town of Hofmeyr, South Africa, the cranium was almost complete, but the bone was degraded. Not enough carbon remained for scientists at the time to extract a radiocarbon date.

Using new technology, Richard Bailey and other researchers at the University of Oxford measured the amount of radiation that had been absorbed by sand grains that had filled the braincase since its burial. They calculated the yearly rate at which radiation had collected in the sand and checked this with data from a CT scan of the bone. In this way, they determined that the Hofmeyr skull belonged to a human who lived 36,000 years ago, plus or minus 3,000 years.

Another member of the team, Katerina Harvati of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, made a detailed examination of the shapes, sizes and contours of all parts of the skull. She compared these three-dimensional measurements with those of early human skulls from Europe and with skulls of living humans in Eurasia and southern Africa, including the Khoe-San, commonly known as the Bushmen.

Because the Bushmen are well represented in the more recent archaeological record, Dr. Harvati said, they were expected to bear a close resemblance to the Hofmeyr skull. Instead, the skull was found to be quite distinct from all recent Africans, including the Bushmen, she said, and it has a very close affinity with fossil specimens of Europeans living in the Upper Paleolithic, the period best known for advanced stone tools and cave art.

Much to my amazement, Dr. Grine said in an interview, the skull linked very closely with those from Europe at the time and not with South African remains 15,000 years on.

Dr. Grine said these modern humans probably originated in East Africa, which is rich in fossils of ancestors of the species, and moved into Eurasia and also south to the tip of Africa.

It would be nice, he conceded, if we had more than one specimen.

Another report in Science describes one of the earliest occupation sites of modern humans in Europe, at Kostenki on the Don River, 250 miles south of Moscow. Its stone and bone tools and a human figurine appeared to have been made about 45,000 years ago, perhaps earlier than human sites to the west.

The lead author of the report was Michael Anikovich of the Russian Academy of Sciences. John Hoffecker of the University of Colorado, a team member, said the small figurine might be the oldest example of figurative art ever discovered.

Dr. Goebel said the new research, archaeology, genetics and the Hofmeyr skull should help explain when and how modern humans leaving Africa spread out to different environments, which, he added, is one of the greatest untold stories in the history of humankind.

Source Link: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/12/science/12skull.html?ex=1169182800&en=5162a3a01555626c&ei=5099&partner=TOPIXNEWS

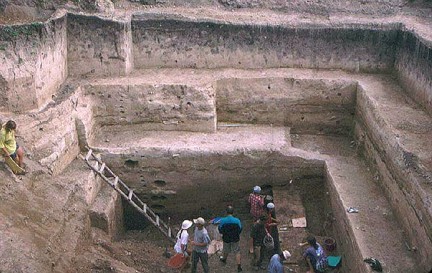

Earliest evidence of modern humans in Europe discovered by international team Stone, bone and ivory artifacts may date back 45,000 years

A research team works at the Kostenki site on the Don River located about 250 miles south of Moscow.

Modern humans who first arose in Africa had moved into Europe as far back as about 45,000 years ago, according to a new study by an international research team led by the Russian Academy of Sciences and the University of Colorado at Boulder.

The evidence consists of stone, bone and ivory tools discovered under a layer of ancient volcanic ash on the Don River in Russia some 250 miles south of Moscow, said John Hoffecker, a fellow of CU-Boulder's Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research. Thought to contain the earliest evidence of modern humans in Europe, the site also has yielded perforated shell ornaments and a carved piece of mammoth ivory that appears to be the head of a small human figurine, which may represent the earliest piece of figurative art in the world, he said.

"The big surprise here is the very early presence of modern humans in one of the coldest, driest places in Europe," Hoffecker said. "It is one of the last places we would have expected people from Africa to occupy first."

A paper by Michael Anikovich and Andrei Sinitsyn of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Hoffecker, and 13 other researchers was published in the Jan. 12 issue of Science.

The excavation took place at Kostenki, a group of more than 20 sites along the Don River that have been under study for many decades. Kostenki previously has yielded anatomically modern human bones and artifacts dating between 30,000 and 40,000 years old, including the oldest firmly dated bone and ivory needles with eyelets that indicate the early inhabitants were tailoring animal furs to help them survive the harsh climate.

Most of the stone used for artifact construction was imported from between 60 miles and 100 miles away, while the perforated shell ornaments discovered at the lowest levels of the Kostenki dig were imported from the Black Sea more than 300 miles away, he said. "Although human skeletal remains in the earliest level of the excavation are confined to isolated teeth, which are notoriously difficult to assign to specific human types, the artifacts are unmistakably the work of modern humans," Hoffecker said.

An assemblage of bone and ivory artifacts from the lowest layer at Kostenki that includes a perforated shell, a probable small human figurine (three views, top center) and several...

The sediment overlying the artifacts was dated by several methods, including an analysis of an ash layer deposited by a monumental volcanic eruption in present-day Italy about 40,000 years ago, Hoffecker said. The researchers also used optically stimulated luminescence dating -- which helps them determine how long ago materials were last exposed to daylight -- as well as paleomagnetic dating based on known changes in the orientation and intensity of Earth's magnetic field and radiocarbon calibration.

Anatomically modern humans are thought to have arisen in sub-Saharan Africa around 200,000 years ago.

Kostenki also contains evidence that modern humans were rapidly broadening their diet to include small mammals and freshwater aquatic foods, an indication they were "remaking themselves technologically," he said. They may have used traps and snares to catch hares and arctic foxes, exploiting large areas of the environment with relatively little energy. "They probably set out their nets and traps and went home for lunch," he said.

While there is some evidence Neanderthals once occupied the plains of Eastern Europe, they seem to have been scarce or absent there during the last glacial period when modern humans arrived, he said. The lack of competitors like the Neanderthals might have been the chief attraction to the area and the reason why modern humans first entered this part of Europe, Hoffecker said.

"Unlike the Neanderthals, modern humans had the ability to devise new technologies for coping with cold climates and less than abundant food resources," he said. "The Neanderthals, who had occupied Europe for more than 200,000 years, seem to have left the back door open for modern humans. "

The ivory artifact believed to be the head of a small figurine, discovered during the 2001 field season, was broken and perhaps never was finished by the person who began crafting it more than 40,000 years ago, said Hoffecker. "This is a really interesting piece," he said. "If confirmed, it will be the oldest example of figurative art ever discovered."

Buried under 10 feet to 15 feet of silt, the artifacts at Kostenki include blades, scrapers, drills and awls, as well as sturdy antler digging tools known as mattocks that resemble crude pick-axes, he said. Mattocks have been found at other Old World sites and the arctic and were used to dig large pits for the storage of foods and fuel, although traces of such pits have yet to turn up at the lowest levels of Kostenki, he said.

Large animal remains at Kostenki include mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, bison, horses, moose and reindeer. A bone chemistry analysis from 30,000-year-old human remains indicates a high consumption of freshwater aquatic foods -- either water birds, fish, or both -- more evidence for efficient food gathering techniques, he said.

Except for some early sites in the Near East, the oldest evidence modern humans outside of Africa comes from the Australian continent roughly 50,000 years ago, said Hoffecker, who was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Russian Academy of Sciences in 2006. Several modern human sites in south-central Europe may be almost as old as Kostenki, he said.

Contact: John Hoffecker, (303) 220-7646

John.Hoffecker@colorado.edu

Jim Scott, (303) 492-3114

Jan. 11, 2007

Editors: Contents embargoed until Thursday, Jan. 11, at 2 p.m. EST.

The study also included researchers from the University of Arizona, the Kostenki Museum-Preserve in Kostenki, the University of Illinois-Chicago, Boston University, the University College London and the Institute of Environmental Geology, Climate and Geoengineering in Rome. Research at Kostenki has been funded by the Leakey Foundation and the National Science Foundation.

Source link: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_

releases/2007-01/uoca-eeo010807.php

Más información:

1 comentario

Fedush -