Mecanismo de Antikythera. El ordenador astronómico más antiguo del mundo revela sus secretos

Una especie de "manual técnico de uso" y otros de los secretos más íntimos del Mecanismo de Antikythera, el ordenador astronómico más antiguo del mundo, estarán a merced de la comunidad científica mundial en noviembre, en un congreso internacional que tendrá lugar en Atenas.

Artículo relacionado: Antikythira, la primera calculadora de la historia

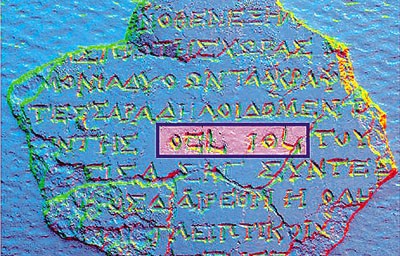

La cita representará el culmen de las investigaciones de un equipo de científicos greco-británico, que lograron sacar a la luz una serie de inscripciones disimuladas en el Mecanismo -que data del año 87 a.C.- y que habían permanecido disimuladas en sus entrañas desde hace más de 2.000 años.

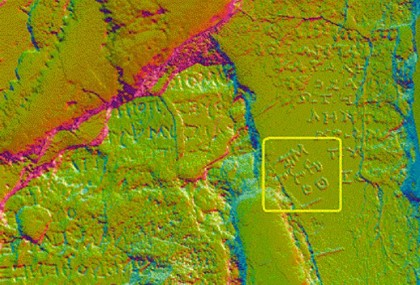

"Más de 1.000 caracteres incluidos en la máquina ya habían sido descifrados pero ahora logramos duplicar el texto conocido y descifrar su contenido en un 95%", declaró a AFP el físico Iannis Bitsakis, uno de los participantes en la investigación organizada por la universidad británica de Cardiff.

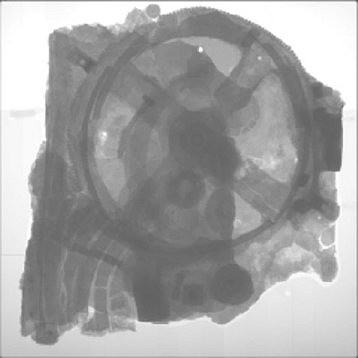

Un escáner especial de ocho toneladas fue el que obligó al Mecanismo de Antikythera, que data del año 87 a.C., a desvelar esos contenidos celosamente escondidos y entre los que también hay valiosos textos de astronomía escritos en griego antiguo.

El gigantesco escáner -financiado en su mayor parte por empresas privadas- logró fotografiar en tres dimensiones el Mecanismo sin que éste tuviese que abandonar el Museo Arqueológico de Atenas, donde se encuentra expuesto.

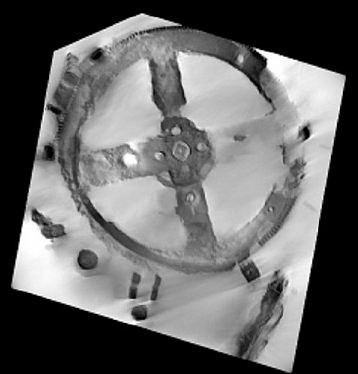

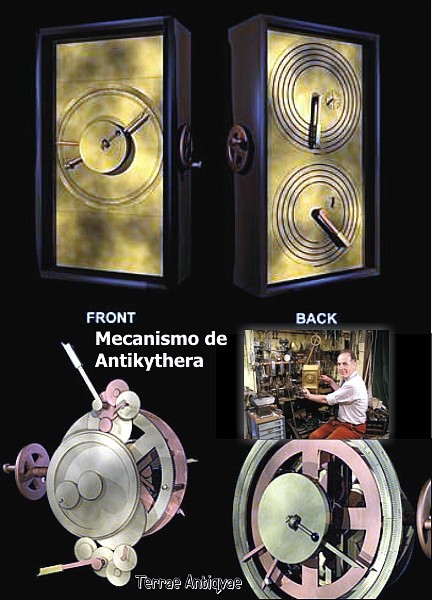

Así quedó al descubierto el funcionamiento interno de ese pequeño artilugio de bronce contenido en un recipiente de madera con forma de caja de zapatos, que constituye la máquina mecánica más antigua del planeta.

Con tan sólo 20 centímetros de espesor, "muy raro si no único", el Mecanismo de Antikythera "fue una especie de sucesor de los menhires y los círculos de piedra" prehistóricos, explicó el astrofísico griego Xenophon Mussas.

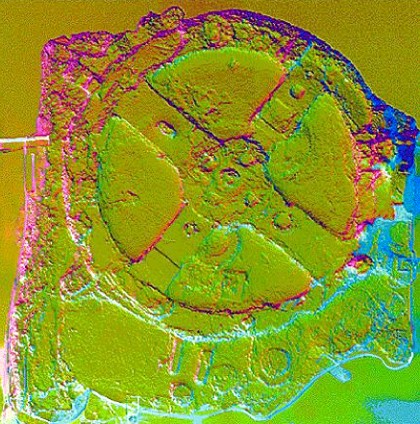

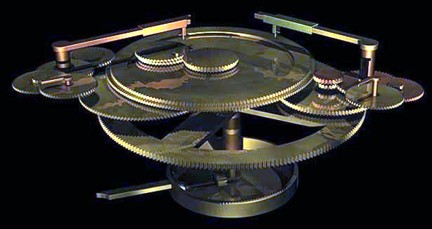

Según lo puesto de manifiesto por las fotografías, el Mecanismo -que fue hallado en 1900 en un barco hundido en aguas de la isla griega de Antikythera- está constituido por cinco cuadrantes, agujas móviles y unas 30 ruedas dentadas, movidas, con toda probabilidad, por una manivela.

El primer gran estudio sobre el aparato, realizado en los años 60 por el historiador inglés Derek Price, reveló que el Mecanismo era "un ordenador astronómico con el que se calculaba la posición de los cuerpos celestes, al menos del Sol y la Luna, y se preveían fenónemos astronómicos".

Esta hipótesis, sin embargo, plantea una serie de interrogantes a los que la investigación greco-británica intentó dar respuesta.

"El rompecabezas que tenemos que reconstruir afecta también a los conocimientos astronómicos y matemáticos del mundo antiguo, cuya historia podría esclarecer el Mecanismo", subrayó Mussas.

"Uno de los desafíos es situar en un contexto científico este Mecanismo, que no se sabe muy bien de dónde viene y contradice las hipótesis según las cuales los griegos no controlaban demasiado bien la técnica", añadió Bistakis.

Los investigadores también empezaron a estudiar otros vestigios encontrados en la misma nave que el Mecanismo, en un intento de probar las hipótesis fundadas en descripciones de Cicerón, según las cuales el instrumento fue construido por el filósofo estoico griego Poseidonios, que creó una prestigiosa escuela astronómica en la isla de Rodas, al sureste del mar Egeo.

"Al igual que Alejandría, Rodas era en aquella época uno de los grandes centros de la astronomía; puede ser que el instrumento estuviese siendo enviado a Roma como muestra de los tesoros que César se llevó de esa isla griega", dijo Mussas.

Fuente: AFP, 6 de junio de 2006

Enlace: http://actualidad.tiscali.es/articulo.jsp?pos=9&sub=1&content=466302

***Enlaces recomendados:

http://www.xtekxray.com/antikythera.htm

The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project

http://www.antikythera-mechanism.gr/

http://www.hpl.hp.com/research/ptm/

antikythera_mechanism/index.html

-----------------------------

X-Tek inspects ancient computer

X-Tek Systems has put its industrial x-ray capabilities to work to inspect a piece of computational equipment. But the equipment in question doesnt contain BGAs whose solder-ball integrity must be verified. Instead, it was manufactured around 80 BC and was probably used to perform astronomical calculations.

The company reports that its equivalent of a body scanner has been used to probe the secrets of the ancient artifact. Discovered in 1900 AD in a shipwreck in the Greek islands, the Antikythera mechanism contains over 30 gear wheels and dials, and it is covered in astronomical inscriptions. It may have been used to demonstrate the motion of the sun, moon, and planets, or to calculate calendars or astrological events. Although the mechanism is no bigger than a shoe box, its too valuable to leave the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, so, at the end of last year, X-Tek sent a unique 400-kV microfocus computed tomography system, weighing over 7.5 tons, to Greece for use in examining the artifact.

X-Teks imaging equipment has enabled researchers to view inscriptions inside the mechanism, which havent been seen for over 2000 years, and work is continuing on counting the gear teeth and deciphering the inscriptions. Looking at the data with X-Tek, academic principal investigator professor Mike Edmunds commented, The outstanding results obtained from X-Teks 3-D x-rays are allowing us to make a definitive investigation of the mechanism. I do not believe it will ever be possible to do better.

X-Teks managing director Roger Hadland added, We are delighted to be able to exhibit the cutting-edge capabilities of our x-ray technology in this way. The project has ably demonstrated that X-Teks x-ray technology, originally developed for industry, can be inventively used for a wealth of other applications.

A final conclusion on the mechanisms purpose is expected after full examination of the data. The investigation is being filmed for a major TV documentary. The Antikythera Research Project is a joint program between Cardiff University, Athens University, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, X-Tek Group, and Hewlett-Packard USA, with funding from the Leverhulme Foundation.

www.xtekxray.com

Antikythera Mechanism

In an exciting link up between high-tech industry and international universities, including Cardiff, Athens and Thessalonika, the secrets of a two-thousand-year-old astronomical calculating device, the Antikythera Mechanism, are exposed for the first time with a unique 400kV microfocus Computed Tomography System.

The Inspection

X-Teks 400kV microfocus CT equipment has been used to probe the secrets of the ancient artefact, estimated to date from around 80 BC. Discovered in 1900 AD in a shipwreck in the Greek islands, the Antikythera Mechanism contains over 30 gear wheels and dials and the remains are covered in astronomical inscriptions. It may be a device to demonstrate the motion of the Sun, Moon and planets, or to calculate calendars or astrological events.

Although the Mechanism is no bigger than a shoe box, its too priceless and unique to leave the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, so a major expedition in late 2005 brought an X-ray tomography machine, weighing over 7.5 tonnes, to examine the artefact in Greece.

As the results of the research are analysed, the structure and purpose of the mechanism, now in dozens of fragments, will become clearer. X-Teks imaging equipment has enabled researchers to view inscriptions inside the Mechanism which havent been seen for over 2,000 years and work can now continue on counting the gear teeth and deciphering the inscriptions. Looking at the data with X-Tek, academic principal investigator Professor Mike Edmunds commented, "The outstanding results obtained from X-Teks 3-D x-rays are allowing us to make a definitive investigation of the Mechanism. I do not believe it will ever be possible to do better."

X-Teks Managing Director Roger Hadland added, "We are delighted to be able to exhibit the cutting-edge capabilities of our X-ray technology in this way." The project has ably demonstrated that X-Teks X-ray technology, originally developed for industry, can be inventively used for a wealth of other applications.

A final conclusion on the Mechanisms purpose is expected in 2006, after full examination of the data. The investigation continues to be filmed for a major TV documentary.

The Antikythera Research Project is a joint programme between Cardiff University, Athens University, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, X-Tek Systems UK and Hewlett-Packard USA, funded by the Leverhulme Foundation.

For more information please contact:

Professor M.G. Edmunds,

Cardiff University

E: mge@astro.cf.ac.uk

T: +44 (0)29 2087 4043

or e-mail: antikythera@xtekxray.com

or visit the official Antikythera Mechanism Research Project website.

Fuente: © 2006 X-Tek Group

Enlace: http://www.xtekxray.com/antikythera.htm

30 de noviembre de 2006

Un grupo de científicos descifra cómo funcionaba una calculadora astronómica griega.

El Mecanismo Antikythera, descubierto hace más de 100 años en un naufragio romano, fue utilizado por los griegos antiguos para mostrar los ciclos astronómicos. Utilizando técnicas avanzadas, un equipo anglo-griego investigó los fragmentos restantes del complejo instrumento. Los resultados, publicados en la revista académica Science, muestran que podría haber sido usado para predecir eclipses solares y lunares y obtener información planetaria.

"Es tan importante para la tecnología como la Acrópolis para la arquitectura", ha declarado el profesor John Seiradakis, de la Universidad Aristóteles en la ciudad griega de Thesssaloniki, y uno de los integrantes del equipo. "Es un instrumento único". Sin embargo, no todos los expertos están de acuerdo con esa interpretación del mecanismo.

Complejidad técnica

Los restos del instrumento fueron descubiertos en 1902 cuando el arqueólogo Valerios Stais notó una rueda de engranaje fuertemente corroída entre unos artefactos rescatados de un barco romano hundido. Desde entonces, otros 81 fragmentos han sido encontrados que contienen un total de 30 engranajes de bronce cortados a mano de los cuales el fragmento más grande tiene 27 piñones.

Los investigadores creen que estos habrían estado encajados en un marco rectangular de madera con dos puertas, cubiertas con instrucciones para su uso y qye la calculadora completa habría sido impulsada por una manivela.

Pese a que sus orígenes son inciertos, nuevos estudios de las inscripciones sugieren que habría sido construida alrededor de los años 100-150 antes de Cristo, mucho antes que instrumentos similares apareciesen en otras partes del mundo.

El equipo de investigadores ha escrito en Nature que el mecanismo era "técnicamente más complejo que cualquier otro instrumento conocido al menos en el siguiente milenio". Aunque una buena parte del artefacto se perdió, especialmente su parte frontal, lo que queda le ha dado material a los investigadores por más de un siglo para obtener una ventana al mundo de la astronomía griega antigua.

Uno de los estudios más completos fue llevado a cabo por el historiador de la ciencia británico Derek Solla Price, quien sostuvo la teoría de que el instrumento era utilizado para calcular y mostrar información celestial. Esto habría sido importante para establecer el cronograma de festivales agrícolas y religiosos.

Recientemente, algunos investigadores sostienen que podría haber sido usado para enseñar o para la navegación y es que, aunque el trabajo de Solla hizo bastante por avanzar el estado del conocimiento sobre las funciones del instrumento, sus interpretaciones acerca de la mecánica han sido descartadas casi en su totalidad en tiempos más recientes. Por ejemplo, una reinterpretación de los fragmentos por Michael Wright, de la universidad Imperial College de Londres, llevada a cabo entre 2002 y 2005, por ejemplo, propuso un modelo de ensamblaje enteramente distinto para los engranajes.

Función de eclipse

Utilizando equipos especialmente diseñados, el equipo pudo tomar fotos detalladas del instrumento y descubrir nueva información. La estructura principal que describen, al igual que lo hacen estudios anteriores, tenía un dial único, ubicado centralmente en el plato frontal que mostraba el zodiaco griego y un calendario egipcio en escalas concéntricas.

Al respaldo, dos diales adicionales mostraban información acerca de la duración de los ciclos lunares y los patrones de eclipses. Previamente, la idea de que el mecanismo podía predecir eclipses era apenas una hipótesis.

Muestra planetaria

El equipo también pudo descifrar más del texto en el mecanismo, doblando la cantidad de texto que puede ser leída ahora. Combinadas con el análisis de los diales, las inscripciones sugieren la posibilidad de que el mecanismo pudiese haber sido usado para mostrar las órbitas planetarias. "Inscripciones mencionan la palabra Venus y la palabra ?estacionario? lo que tiende a sugerir que estaba mirando a los movimientos de planetas", señaló el profesor Mike Edmunds. "En mi propia opinión, probablemente mostraba a Venus y Mercurio pero algunas personas sugieren que puede mostrar a otros planetas".

Una de esas personas es Michael Wright. Su reconstrucción del instrumento, con 72 engranajes, sugiere que podría haber mostrado los movimientos de los cinco planetas conocidos en ese tiempo.

Fuente: ELPAIS.com/BBCMundo - Madrid - 30/11/2006

Enlace: http://www.elpais.com/articulo/sociedad/calcul

adora/000/anos/elpepusoc/20061130elpepusoc_2/Tes

(2) In search of lost time

The ancient Antikythera Mechanism doesn't just challenge our assumptions about technology transfer over the ages it gives us fresh insights into history itself.

By: Jo Marchant, Photos: J. MARCHANT/ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM RESEARCH PROJECT

It looks like something from another world nothing like the classical statues and vases that fill the rest of the echoing hall. Three flat pieces of what looks like green, flaky pastry are supported in perspex cradles. Within each fragment, layers of something that was once metal have been squashed together, and are now covered in calcareous accretions and various corrosions, from the whitish tin oxide to the dark bluish green of copper chloride. This thing spent 2,000 years at the bottom of the sea before making it to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, and it shows.

But it is the details that take my breath away. Beneath the powdery deposits, tiny cramped writing is visible along with a spiral scale; there are traces of gear-wheels edged with jagged teeth. Next to the fragments an X-ray shows some of the object's internal workings. It looks just like the inside of a wristwatch.

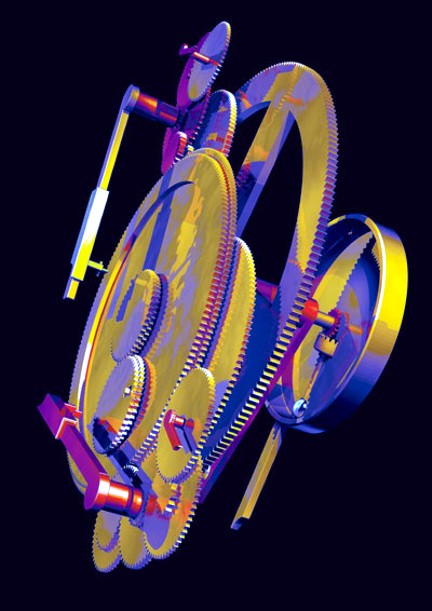

This is the Antikythera Mechanism. These fragments contain at least 30 interlocking gear-wheels, along with copious astronomical inscriptions. Before its sojourn on the sea bed, it computed and displayed the movement of the Sun, the Moon and possibly the planets around Earth, and predicted the dates of future eclipses. It's one of the most stunning artefacts we have from classical antiquity.

No earlier geared mechanism of any sort has ever been found. Nothing close to its technological sophistication appears again for well over a millennium, when astronomical clocks appear in medieval Europe. It stands as a strange exception, stripped of context, of ancestry, of descendants.

Considering how remarkable it is, the Antikythera Mechanism has received comparatively scant attention from archaeologists or historians of science and technology, and is largely unappreciated in the wider world. A virtual reconstruction of the device, published by Mike Edmunds and his colleagues in this week's Nature (see 'Decoding the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism'), may help to change that. With the help of pioneering three-dimensional images of the fragments' innards, the authors present something close to a complete picture of how the device worked, which in turn hints at who might have been responsible for building it.

But I'm also interested in finding the answer to a more perplexing question once the technology arose, where did it go to? The fact that such a sophisticated technology appears seemingly out of the blue is perhaps not that surprising records and artefacts from 2,000 years ago are, after all, scarce. More surprising, to an observer from the progress-obsessed twenty-first century, is the apparent lack of a subsequent tradition based on the same technology of ever better clockworks spreading out round the world. How can the capacity to build a machine so magnificent have passed through history with no obvious effects?

Astronomic leaps

To get an idea of what the mechanism looked like before it had the misfortune to find itself on a sinking ship, I went to see Michael Wright, a curator at the Science Museum in London for more than 20 years and now retired. Stepping into Wright's workshop in Hammersmith is a little like stepping into the workshop where H. G. Wells' time machine was made. Every inch of floor, wall, shelf and bench space is covered with models of old metal gadgets and devices, from ancient Arabic astrolabes to twentieth-century trombones. Over a cup of tea he shows me his model of the Antikythera Mechanism as it might have been in his pomp. The model and the scholarship it embodies have consumed much of his life (see 'Raised from the depths').

The mechanism is contained in a squarish wooden case a little smaller than a shoebox. On the front are two metal dials (brass, although the original was bronze), one inside the other, showing the zodiac and the days of the year. Metal pointers show the positions of the Sun, the Moon and five planets visible to the naked eye. I turn the wooden knob on the side of the box and time passes before my eyes: the Moon makes a full revolution as the Sun inches just a twelfth of the way around the dial. Through a window near the centre of the dial peeks a ball painted half black and half white, spinning to show the Moon's changing phase.

On the back of the box are two spiral dials, one above the other. A pointer at the centre of each traces its way slowly around the spiral groove like a record stylus. The top dial, Wright explains, shows the Metonic cycle 235 months fitting quite precisely into 19 years. The lower spiral, according to the research by Edmunds and his colleagues, was divided into 223, reflecting the 223-month period of the Saros cycle, which is used to predict eclipses.

It's a popular notion that technological development is a simple progression. But history is full of surprises. François Charette

To show me what happens inside, Wright opens the case and starts pulling out the wheels. There are 30 known gear-wheels in the Antikythera Mechanism, the biggest taking up nearly the entire width of the box, the smallest less than a centimetre across. They all have triangular teeth, anything from 15 to 223 of them, and each would have been hand cut from a single sheet of bronze. Turning the side knob engages the big gear-wheel, which goes around once for every year, carrying the date hand. The other gears drive the Moon, Sun and planets and the pointers on the Metonic and Saros spirals.

To see the model in action is to want to find out who had the ingenuity to design the original. Unfortunately, none of the copious inscriptions is a signature. But there are other clues. Coins found at the site by Jacques Cousteau in the 1970s have allowed the shipwreck to be dated sometime shortly after 85 BC. The inscriptions on the device itself suggest it might have been in use for at least 15 or 20 years before that, according to the Edmunds paper.

Photo: Gearing up: this reconstruction shows, among other things, the offset wheels of the Moon's nine-year cycle (lower left). A labelled diagram is on 'Archaeology: High tech from Ancient Greece'. ANTIKYTHERA MECHANISM RESEARCH PROJECT

The ship was carrying a rich cargo of luxury goods, including statues and silver coins from Pergamon on the coast of Asia Minor and vases in the style of Rhodes, a rich trading port at the time. It went down in the middle of a busy shipping route from the eastern to western Aegean, and it seems a fair bet that it was heading west for Rome, which had by that time become the dominant power in the Mediterranean and had a ruling class that loved Greek art, philosophy and technology.

The Rhodian vases are telling clues, because Rhodes was the place to be for astronomy in the first and second centuries BC. Hipparchus, arguably the greatest Greek astronomer, is thought to have worked on the island from around 140 BC until his death in around 120 BC. Later the philosopher Posidonius set up an astronomy school there that continued Hipparchus' tradition; it is within this tradition that Edmunds and his colleagues think the mechanism originated. Circumstantial evidence is provided by Cicero, the first-century BC Roman lawyer and consul. Cicero studied on Rhodes and wrote later that Posidonius had made an instrument "which at each revolution reproduces the same motions of the Sun, the Moon and the five planets that take place in the heavens every day and night". The discovery of the Antikythera Mechanism makes it tempting to believe the story is true.

And Edmunds now has another reason to think the device was made by Hipparchus or his followers on Rhodes. His team's three-dimensional reconstructions of the fragments have turned up a new aspect of the mechanism that is both stunningly clever and directly linked to work by Hipparchus.

One of the wheels connected to the main drive wheel moves around once every nine years. Fixed on to it is a pair of small wheels, one of which sits almost but not exactly on top of the other. The bottom wheel has a pin sticking up from it, which engages with a slot in the wheel above. As the bottom wheel turns, this pin pushes the top wheel round. But because the two wheels aren't centred in the same place, the pin moves back and forth within the upper slot. As a result, the movement of the upper wheel speeds up and slows down, depending on whether the pin is a little farther in towards the centre or a little farther out towards the tips of the teeth (see illustration on 'Archaeology: High tech from Ancient Greece').

The researchers realized that the ratios of the gear-wheels involved produce a motion that closely mimics the varying motion of the Moon around Earth, as described by Hipparchus. When the Moon is close to us it seems to move faster. And the closest part of the Moon's orbit itself makes a full rotation around the Earth about every nine years. Hipparchus was the first to describe this motion mathematically, working on the idea that the Moon's orbit, although circular, was centred on a point offset from the centre of Earth that described a nine-year circle. In the Antikythera Mechanism, this theory is beautifully translated into mechanical form. "It's an unbelievably sophisticated idea," says Tony Freeth, a mathematician who worked out most of the mechanics for Edmunds' team. "I don't know how they thought of it."

"I'm very surprised to find a mechanical representation of this," adds Alexander Jones, a historian of astronomy at the University of Toronto, Canada. He says the Antikythera Mechanism has had little impact on the history of science so far. "But I think that's about to change. This was absolutely state of the art in astronomy at the time."

Wright believes that similar mechanisms modelled the motions of the five known planets, as well as of the Sun, although this part of the device has been lost. As he cranks the gears of his model to demonstrate, and the days, months and years pass, each pointer alternately lags behind and picks up speed to mimic the astronomical wanderings of the appropriate sphere.

Greek tragedy

Almost everyone who has studied the mechanism agrees it couldn't have been a one-off it would have taken practice, perhaps over several generations, to achieve such expertise. Indeed, Cicero wrote of a similar mechanism that was said to have been built by Archimedes. That one was purportedly stolen in 212 BC by the Roman general Marcellus when Archimedes was killed in the sacking of the Sicilian city of Syracuse. The device was kept as an heirloom in Marcellus' family: as a friend of the family, Cicero may indeed have seen it.

So where are the other examples? A model of the workings of the heavens might have had value to a cultivated mind. Bronze had value for everyone. Most bronze artefacts were eventually melted down: the Athens museum has just ten major bronze statues from ancient Greece, of which nine are from shipwrecks. So in terms of the mechanism, "we're lucky we have one", points out Wright. "We only have this because it was out of reach of the scrap-metal man."

But ideas cannot be melted down, and although there are few examples, there is some evidence that techniques for modelling the cycles in the sky with geared mechanisms persisted in the eastern Mediterranean. A sixth-century AD Byzantine sundial brought to Wright at the Science Museum has four surviving gears and would probably have used at least eight to model the positions of the Sun and Moon in the sky. The rise of Islam saw much Greek work being translated into Arabic in the eighth and ninth centuries AD, and it seems quite possible that a tradition of geared mechanisms continued in the caliphate. Around AD 1000, the Persian scholar al-Biruni described a "box of the Moon" very similar to the sixth-century device. There's an Arabic-inscribed astrolabe dating from 122122 currently in the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford, UK, which used seven gears to model the motion of the Sun and Moon.

But to get anything close to the Antikythera Mechanism's sophistication you have to wait until the fourteenth century, when mechanical clockwork appeared all over western Europe. "You start to get a rash of clocks," says Wright. "And as soon as you get clocks, they are being used to drive astronomical displays." Early examples included the St Albans clock made by Richard Wallingford in around 1330 and a clock built by Giovanni de'Dondi a little later in Padua, Italy, both of which were huge astronomical display pieces with elaborate gearing behind the main dial to show the position of the Sun, Moon, planets and (in the case of the Padua clock) the timing of eclipses. The time-telling function seems almost incidental.

It could be argued that the similarities between the medieval technology and that of classical Greece represent separate discoveries of the same thing a sort of convergent clockwork evolution. Wright, though, favours the idea that they are linked by an unbroken tradition: "I find it as easy to believe that this technology survived unrecorded, as to believe that it was reinvented in so similar a form." The timing of the shift to the West might well have been driven by the fall of Baghdad to the Mongols in the thirteenth century, after which much of the caliphate's knowledge spread to Europe. Shortly after that, mechanical clocks appeared in the West, although nobody knows exactly where or how. It's tempting to think that some mechanisms, or at least the ability to build them, came west at the same time. As François Charette, a historian of science at Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, Germany, points out, "for the translation of technology, you can't rely solely on texts". Most texts leave out vital technical details, so you need skills to be transmitted directly.

But if the tradition of geared mechanisms to show astronomical phenomena really survived for well over a millennium, the level of achievement within that tradition was at best static. The clockwork of medieval Europe became more sophisticated and more widely applied fairly quickly; in the classical Mediterranean, with the same technology available, nothing remotely similar happened. Why didn't anyone do anything more useful with it in all that time? More specifically, why didn't anyone work out earlier what the gift of hindsight seems to make obvious that clockwork would be a good thing to make clocks with?

Serafina Cuomo, a historian of science at Imperial College, London, thinks that it all depends on what you see as 'useful'. The Greeks weren't that interested in accurate timekeeping, she says. It was enough to tell the hour of the day, which the water-driven clocks of the time could already do fairly well. But they did value knowledge, power and prestige. She points out that there are various descriptions of mechanisms driven by hot air or water and gears. But instead of developing a steam engine, say, the devices were used to demonstrate philosophical principles. The machines offered a deeper understanding of cosmic order, says David Sedley, a classicist at the University of Cambridge, UK. "There's nothing surprising about the fact that their best technology was used for demonstrating the laws of astronomy. It was deep-rooted in their culture."

Another, not mutually exclusive, theory is that devices such as the Antikythera Mechanism were signifiers of social status. Cuomo points out that demonstrating wondrous devices brought social advancement. "They were trying to impress their peers," she says. "For them, that was worth doing." And the Greek élite was not the only potential market. Rich Romans were eager for all sorts of Greek sophistication they imported philosophers for centuries.

I find it as easy to believe that this technology survived unrecorded, as to believe that this was reinvented in so similar a form. Michael Wright

Seen in this light, the idea that the Antikythera Mechanism might be expected to lead to other sorts of mechanism seems less obvious. If it already embodied the best astronomy of the time, what more was there to do with it? And status symbols do not follow any clearly defined arc of progress. What's more, the idea that machines might do work may have been quite alien to slave-owning societies such as those of Ancient Greece and Rome. "Perhaps the realization that you could use technology for labour-saving devices took a while to dawn," says Sedley.

There is also the problem of power. Water clocks are thought to have been used on occasion to drive geared mechanisms that displayed astronomical phenomena. But dripping water only provides enough pressure to drive a small number of gears, limiting any such display to a much narrower scope than that of the Antikythera Mechanism, which is assumed to have been handcranked. To make the leap to mechanical clocks, a geared mechanism needs to be powered by something other than a person; it was not until medieval Europe that clockwork driven by falling weights makes an appearance.

Invention's evolution

Bert Hall, a science historian at the University of Toronto in Canada, believes a final breakthrough towards a mechanical weight drive might have come about almost by accident, by adapting a bell-ringing device. A water clock could have driven a hammer or weight mechanism swinging between two bells as an alarm system, until someone realized that the weight mechanism would be a more regular way of driving the clock in the first place. When the new way to drive clocks was discovered, says Hall, "the [clockwork] technology came rushing out of the wings into the new tradition".

Researchers would now love further mechanisms to be unearthed in the historical record. "We hope that if we can bring this to people's attention, maybe someone poking around in their museum might find something, or at least a reference to something," says Edmunds. Early Arabic manuscripts, only a fraction of which have so far been studied, are promising to be fertile ground for such discoveries.

Charette also hopes the new Antikythera reconstruction will encourage scholars to take the device more seriously, and serve as a reminder of the messy nature of history. "It's still a popular notion among the public, and among scientists thinking about the history of their disciplines, that technological development is a simple progression," he says. "But history is full of surprises."

In the meantime, Edmunds' Antikythera team plans to keep working on the mechanism there are further inscriptions to be deciphered and the possibility that more fragments could be found. This week the researchers are hosting a conference in Athens that they hope will yield fresh leads. A few minutes' walk from the National Archaeological Museum, Edmunds' colleagues from the University of Athens, Yanis Bitsakis and Xenophon Moussas, treat me to a dinner of aubergine and fried octopus, and explain why they would one day like to devote an entire museum to the story of the fragments.

"It's the same way that we would do things today, it's like modern technology," says Bitsakis. "That's why it fascinates people." What fascinates me is that where we see the potential of that technology to measure time accurately and make machines do work, the Greeks saw a way to demonstrate the beauty of the heavens and get closer to the gods.

Fuente: Jo Marchant is Natures News Editor. 29 November 2006

Enlace: http://www.nature.com/news/

2006/061127/full/444534a.html

14 comentarios

Diego -

muy buen descubrimiento.. me encantaria haber vivido en esa epoca.. solo pensar q hera un secreto de estado para tener a los ciudadanos de la antigua grecia bajo control, me hace temblar de espanto xq pienso q si en esas epocas tenian esos avances en esta hera q vivimos seguro nos ocultan cosas henormes q ni podemos imaginar.. solo eso puedo agregar a esto.. suerte para todos..

-------------------------------------------

Lo mismo se van a preguntar en 1000 años , se preguntaran como hemos podido trabajar con Windows Xp

margareth daniela -

ioan marin -

ivan -

JOSE ONNIER OSORIO 0. -

Caparrós -

Personalmente pienso que creernos, que en el momento actual, estamos en la cumbre de los descubrimientos técnicos y cientificos, es un gran error. Hay otras influencias...? que si quieren que pensemos eso.

Para los que quieran seguir investigando les dejo una relación de libros que estoy seguro que seran de su interés:

LIBROS de SITCHIN, ZECHARIA

1. EL DUODECIMO PLANETA (EL PRIMER LIBRO DE CRONICA DE LA TIERRA)

EDICIONES OBELISCO, S.A. - Lengua: CASTELLANO - Encuadernación: Rustica - ISBN: 8477208603

437 pgs (16.0x24.0 cm.) 17.00 Traductor: TONI CUTANDA Edición: 1ª, 2002 Barcelona

¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬2. LA ESCALERA AL CIELO (EL SEGUNDO LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA) Crítica: Imprescindible

EDICIONES OBELISCO, S.A. - Lengua: CASTELLANO - Encuadernación: Rustica - ISBN: 8477208964

402 pgs (16.0x24.0 cm.) 17.00 Traductor: TONI CUTANDA Tipo Ilustración: DIBU Edición: 1ª, 2002 Barcelona

3. LA GUERRA DE DIOSES Y HOMBRES (EL TERCER LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA)

_______________________________________________________________________________

4. LOS REINOS PERDIDOS (EL CUARTO LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA)

EDICIONES OBELISCO, S.A. - Lengua: CASTELLANO - Encuadernación: Rustica - ISBN: 8477209243

333 pgs (16.0x24.0 cm.) 17.00 Edición: 1ª, 2002 Barcelona

__________________________________________________________________________________

5. EL CODIGO COSMICO (EL SEXTO LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA)

EDICIONES OBELISCO, S.A. - Lengua: CASTELLANO - Encuadernación: Rustica - ISBN: 8497770560

272 pgs (16.0x25.0 cm.) 15.00 Edición: 1ª, 2003 Barcelona - Traductor: ANTONIO CUTANDA

_______________________________________________________________________________

6. EL LIBRO PERDIDO DE ENKI (Memorias y Profecías de un Dios Extra-terrestre)

(EL SEXTO LIBRO DE LAS CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA)

EDICIONES OBELISCO, S.A. - Lengua: CASTELLANO - Encuadernación: Rustica - ISBN: 8497770552

271 pgs (16.0x25.0 cm.) 14.00 Edición: 1ª, 2003 Barcelona

______________________________________________________________________________________________

7. LAS EXPEDICIONES de CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA Casadellibro.com

EDICIONES OBELISCO, S.A. - Lengua: CASTELLANO - Encuadernación: Rustica - ISBN: 8497772369

304 pgs (15.0x23.0 cm.) 17.00 Tipo ilustración: Foto - Edición: 1ª, 2005 Barcelona

¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬

8. EL GENESIS REVISADO

EDICIONES OBELISCO, S.A. - Lengua: CASTELLANO - Encuadernación: Rustica - ISBN: 8497772253

352 pgs (16.0x24.0 cm.) 16.00 Edición: 1ª, 2005 Barcelona

9. ENCUENTROS DIVINOS (GUIA SOBRE VISIONES, ANGELES Y DEMAS EMISARIOS)

EDICIONES OBELISCO, S.A. - Lengua: CASTELLANO - Encuadernación: Rustica - ISBN: 8497773195

383 pgs 17.00 Edición: 1ª, 2006 Barcelona

___________________________________________________________________________________________

10. AL PRINCIPIO DE LOS TIEMPOS

EDICIONES OBELISCO, S.A. Lengua: CASTELLANO Encuadernación: Rústica - ISBN: 8477209774¬¬

384 pgs (16.0x25.0 cm.) 17.00 Edición: 1ª, 2002 Barcelona - Edición especial de gran formato, ilustrada.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Detalle de los libros que componen la serie: CRÓNICAS DE LA TIERRA

1. EL DUODECIMO PLANETA (EL 1º LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA)

2. LA ESCALERA AL CIELO (EL 2º LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA)

3. La Guerra de Dioses y Hombres (EL 3º LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA)

4. LOS REINOS PERDIDOS (EL 4º LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA)

5. EL CODIGO COSMICO (EL 5º LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TI ERRA)

6. El Libro Perdido de ENKI (EL 6º LIBRO DE CRONICAS DE LA TIERRA) ========================================================================

OTROS MUY INTERESANTES DE OTROS TEMAS Y EDITORIALES:

- Las Sociedades Secretas - Disponible en el Corte Inglés - Edit. Planeta S.A. 2006. ISBN. 84-08-06555-6

- La verdadera historia del Club Bilderberg, - Daniel Estulin Editorial Planeta 2005 ISBN 84-8453-157-0

- El Enigma Sagrado Ediciones Martinez Roca, S.A. 2004 - ISBN 84-270-2756-7

Luiz Cláudio Souza Pinto -

eduardo -

samuel bote -

si esto existia hace mas de 2000 años tendriamos que enfocar los esfuerzos de la ciencia en descubrir artilugios igual de sofisticados de esa epoca o mas antiguos. simpre hemos pensado que los instrumentos mecanicos comenzaron a surgir a partir del invento de los relojes por los siglos XIII y XIV. que equivocados estabamos. esto plantea una realidad completamente nueva y nos hace reflexionar y entusiasmarnos de nuevos descubrimientos por venir.

desde mexico....saludos.

Voss -

walter zarate pflucker -

E.Castilho -

.

Alexs -

Argenis -