El hombre actual y el neandertal, casi iguales. Los genomas de las dos especies son idénticos en, al menos, el 99,5%

Análisis genéticos revelan que el último ancestro común vivió hace unos 700.000 años y no han encontrado rastros de hibridación.

Artículo relacionado: El Hombre de Neandertal vivió en Gibraltar hasta hace 24.000 años

EL HOMÍNIDO EUROPEO

Descubrimiento: Los primeros restos de un neandertal los encontró un niño en la cueva belga de Engis en 1829, aunque no fueron identificados como de una nueva especie hasta 1856.

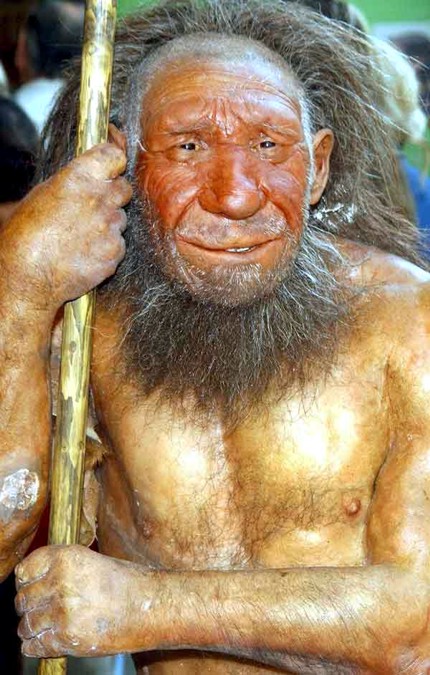

Aspecto: La evolución moldeó la fisionomía de sus antepasados y la de los neandertales para sobrevivir en una Europa fría -cubierta de hielo hasta el norte de Francia-, en la que se daban interludios cálidos de miles de años. Eran más bajos y fornidos que nosotros.

El hombre actual y el neandertal somos casi iguales. Compartimos, al menos, el 99,5% del genoma, según un estudio publicado hoy en la revista 'Science'. «Nuestro parecido genético con el chimpancé (99%) y el neandertal los hace más importantes, porque queda por explicar como tan pocas diferencias nos llevan a ser tan distintos», indica Juan Luis Arsuaga, director del Centro de Evolución y Comportamiento Humanos de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid y el Instituto de Salud Carlos III. «Como se trata de una comparación con los genomas del chimpancé y el ser humano, no me extrañaría que nuestro parecido acabara siendo del 99,7 ó 99,8%», precisa José María Bermúdez de Castro, director del Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana, que abrirá sus puertas en Burgos en 2007.

Los neandertales fueron descubiertos hace 150 años. Vivieron entre hace 400.000 y 30.000 años en Europa, y se extinguieron poco después de la llegada de nuestra especie, el 'Homo sapiens', desde África. El homínido europeo evolucionó a partir de inmigrantes africanos que habían venido en una primera oleada hace más de un millón de años y tenía una capacidad craneal mayor que la del hombre actual. La arqueología ha demostrado que desarrolló una cultura propia, socorría a los heridos y atendía a los enfermos, y alcanzó una adaptabilidad que le permitió sobrevivir en una Europa hostil, de clima cambiante, durante decenas de miles de años. Y, de repente, hace 30.000 años, desapareció. Los expertos creen que fue porque perdió la guerra por los recursos con una especie invasora, nosotros.

Separación de las estirpes

Dos investigaciones publicadas hoy en 'Nature' y 'Science' suponen un primer vistazo genético a nuestro pariente más próximo. Un grupo de científicos estadounidenses y alemanes liderado por Edward Rubin, del Laboratorio Nacional Lawrence Berkeley, de EE UU, concluye en 'Science' que el neandertal se parece a nosotros en, como poco, el 99,5% del genoma, según el análisis de 65.250 pares de bases del ADN de un fósil de hace 38.000 años descubierto en Vindija (Croacia). Los secretos de las diferencias entre las dos especies están, por tanto, en el 0,5% del genoma.

El trabajo de Rubin establece que el último antepasado común del 'Homo sapiens' y el neandertal vivió hace 706.000 años y que las estirpes de ambas especies se separaron definitivamente -no era ya posible la reproducción entre ellas- hace 370.000 años, mucho antes de la aparición de los primeros 'H. sapiens' en lo que hoy es Etiopía. A partir del estudio de un millón de pares de bases procedentes del mismo fósil, otro trabajo dirigido por Svante Pääbo, del Instituto Max Planck de Antropología Evolutiva de Leipzig, sitúa la divergencia entre las dos estirpes hace 500.000 años, .

«Casa con lo que veníamos diciendo los paleoantropólogos», afirma Arsuaga, codirector de las excavaciones de Atapuerca. Bermúdez de Castro cree que, si 'Homo antecessor' -la especie descubierta en la sierra de Burgos - no es ese antepasado común entre los neandertales y nosotros, «está cerquísima, porque la cara moderna no se la quita nadie». Tras el inicio de la separación de las estirpes, serían en los 'Homo heidelbergensis' de Europa y África en los que se completaría la evolución hacia neandertales y 'sapiens', respectivamente. Durante decenas de miles de años, seguirían siendo una especie hasta romper definitivamente hace unos 370.000 años.

Los dos trabajos concluyen, asimismo, que no hay pruebas de hibridación entre los dos homínidos. «Es lo que sabíamos. No tenemos ascendientes neandertales», sentencia Arsuaga, para quien, si alguna vez hubo mestizaje, los genes neandertal desaparecieron en nuestra especie de la misma forma que los apellidos poco comunes, con el tiempo. «No excluimos la posibilidad de una modesta aportación a nuestra genoma», advierte Jonathan Pritchard, de la Universidad de Chicago y uno de los autores. Los trabajos publicados hoy, dicen los investigadores, marcan «el amanecer de la genómica neandertal». «Si podemos comparar los genomas del hombre y del neandertal, podremos identificar cuáles fueron los cambios genéticos claves durante la fase final de la evolución humana», sentencia Pritchard.

Fuente: LUIS ALFONSO GÁMEZ l/BILBAO l.a.gamez@diario-elcorreo.c

Diario Vasco, 16 de noviembre de 2006

Enlace: http://www.elcorreodigital.com/vizcaya/prensa/20061116/sociedad/hombre-actual-neandertal-casi_20061116.html

(2) Scientists decode Neanderthal genes

Material from 38,000-year-old bone fragment being analyzed

By Ker Than

Humans and their close Neanderthal relatives began diverging from a common ancestor about 700,000 years ago, and the two groups split permanently some 300,000 years later, according to two of the most detailed analyses of Neanderthal DNA to date.

Photo: A reconstructed Neanderthal skeleton, right, and a modern version of a Homo sapiens skeleton are on display at the Museaum of Natural History Wednesday, Jan. 8, 2003 in New York. The Neanderthal skeleton, reconstructed from casts of more than 200 Neanderthal fossil bones, is part of the museum's exhibit called "The First Europeans: Treasures from the Hills of Atapuerca." (AP Photo/Frank Franklin II) 1:02 p.m. ET, 11/15/06

Using different techniques, two teams of scientists separately sequenced large chunks of DNA extracted from the femur of a 38,000-year-old Neanderthal specimen found in a cave 26 years ago in Croatia. One team sequenced more than 1 million base pairs of the 3.3-billion-pair genome, and the other analyzed 65,000 pairs.

The achievements could help shed light on the evolution of our own species, and it paves the way for building a complete library of the Neanderthal genome within a few years, the scientists say.

No evidence of interbreeding

In popular imagination, Neanderthals are often portrayed as prehistoric brutes who became outsmarted by a more advanced species, humans, emerging from Africa. But excavations and anatomical studies have shown that Neanderthals used tools, wore jewelry, buried their dead, cared for their sick, and possibly sang or even spoke in much the same way that we do. Even more humbling, perhaps, their brains were slightly larger than ours.

The results from the new studies confirm the Neanderthal's humanity, and show that their genomes and ours are more than 99.5 percent identical, differing by only about 3 million bases.

"This is a drop in the bucket if you consider that the human genome is 3 billion bases," said Edward Rubin of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, who led one of the research teams.

For comparison, the genomes of chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, differ from humans by about 30 million to 50 million base pairs.

The findings also appear to argue against speculations by some scientists that Neanderthals and humans interbred in more recent times. "We see no evidence of mixing 30,000 to 40,000 years ago in Europe," Rubin said. "We don't exclude it, but from the data that we have, we have no evidence that pages were ripped from one genome and put in the other."

Ruling out contamination

One of the biggest challenges in sequencing Neanderthal DNA is finding a bone sample that hasn't been too contaminated by human handling. Fortunately, the femur fragment used in the studies was relatively small and uninteresting, causing it to be largely overlooked.

The femur "was thrown in a big box of uninformative bones and not handled very much," said Svante Paabo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, leader of the other sequencing project. "Whereas more interesting bones where you can study the muscle attachment and the morphology of Neanderthals had been extensively cleaned and handled and thus tend to be much more contaminated."

The researchers also relied on other clues, such as chemical damage unique to ancient DNA, to help verify that the genetic material was indeed Neanderthal. "One of the crucial things is that we feel confident that the DNA we have, which we're calling Neanderthal, is truly Neanderthal," Rubin said.

New advances

The successes of the two teams' sequencing projects were made possible by recent advances in DNA sequencing technology, which now allow scientists to sequence DNA more than 100 times faster than in the past.

Paabo's team recovered more than a million Neanderthal base pairs using a new automated technique called "pyrosequencing." In this process, DNA fragments are attached to tiny artificial beads, sequenced, and then matched to similar sections on human chromosomes.

Rubin's team employed "metagenomics," which involves integrating short fragments of extracted Neanderthal DNA into the genomes of bacteria. The Neanderthal DNA gets amplified as the bacteria divide, and then scientists pluck out human-matching bases using "probes" made with snippets of human DNA.

The researchers say their achievements mark the "dawn of Neanderthal genomics," and they estimate that further advances in DNA sequencing technology could allow the completion of a very rough draft of the entire Neanderthal genome within two years.

"There's no question that we're going to have a Neanderthal genome, and likely, we're going to have several Neanderthal genomes," Rubin said. The team hopes to extract and sequence DNA from the bones of other individuals and to complete several drafts of the Neanderthal genome.

Clues to our past

A complete Neanderthal genome would help scientists identify the genetic changes in our own genome that set us apart from other hominids.

The comparison between recently sequenced chimpanzee genomes and ours is already shedding light on the evolutionary changes our ancestors went through to make them less ape-like. But because chimps and humans began diverging some 6.5 million years ago, examination of their genome cannot reveal what happened in the final stretches of our own evolution.

"Humans went through several stages of evolution in the last 400,000 years," said study co-author Jonathan Pritchard of the University of Chicago. "If we can compare humans and Neanderthals genomes, then we can possibly identify what the key genetic changes were during that final stage of human evolution."

A completed genome will also reveal new insights about Neanderthals, who disappeared mysteriously about 30,000 years ago.

"In having the Neanderthal genome sequence ...we're going to learn about the biology, learn about things that we could never learn from the bones and the artifacts that we have," Rubin said.

The results of Rubin's team are detailed in Thursday's issue of the journal Nature; Paabo's team's results are detailed in Friday's issue of the journal Science.

Fuente: LiveScience.com / MSNBC.com, 15 de noviembre de 2006

Enlace: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15732243/

Artículos relacionados:

http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/97/13/7663

http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/96/22/12281

http://www.americanscientist.org/template/AssetDetail

/assetid/28338/page/1;jsessionid=aaa5LVF0

0 comentarios