Arqueólogos hallan dos líneas de alfabeto hebreo antiguo

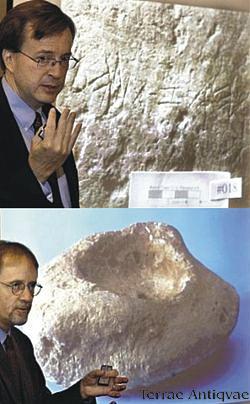

Foto: (1) P. Kyle McCarter, an epigrapher and professor of Ancient Near Eastern Studies at John Hopkins University, talks about the significance of the alphabet found on a rock at the Zeitah Excavations archaeological dig at Tel Zayat, Israel, during a news conference in Pittsburgh on Wednesday, Nov. 9, 2005. A magnified image of letters from 900-925 BC on that rock, which was found in July at the dig, is projected behind him. (AP Photo/Keith Srakocic) (2) Ron E. Tappy, the project director of the Zeitah Excavations archaeological dig at Tel Zayat, Israel, speaks at a news conference in Pittsburgh on Wednesday, Nov. 9, 2005, about the discovery in July at the dig of a rock from 900-925 BC, that has an alphabet inscribed upon it. An image of the rock that was part of a wall is projected behind him. (AP Photo/Keith Srakocic)

PITTSBURGH, Pensilvania, EE.UU. (AP) _ Dos líneas escritas en un alfabeto antiguo, que aparecen inscritas sobre una tablilla de piedra, darán renovado impulso al debate acerca de si los antiguos hebreos conocían la escritura, afirman expertos.

Los académicos sostienen que el descubrimiento del arqueólogo de Pittsburgh Ron E. Tappy, profesor del Seminario Teológico de Pittsburgh, es la prueba más concreta de que los antiguos israelitas conocían la escritura ya en el siglo X a. C.

"Esto es algo muy desusado", dijo Tappt el miércoles en rueda de prensa. "Esta piedra será tema de artículos durante muchos años. Esto hace muy probable, históricamente, que hubiera pueblos que supieran escribir en el siglo X".

Christopher Rollston, un profesor asociado de estudios semíticos en la Escuela Emmanuel de Religión en Johnson City, Tenesí, que no estuvo involucrado en el descubrimiento, dijo que la escritura es similar a la fenicia o que se trata quizá de un idioma de transición entre el fenicio y el hebreo.

La tablilla fue hallada durante excavaciones realizadas en junio en Tel Zayit, en las tierras bajas de Judea, Israel.

"Todos los alfabetos posteriores del mundo antiguo, incluyendo el griego, se derivan de este antepasado de Tel Zayit", dijo Tappy al diario The New York Times en declaraciones publicadas el miércoles.

Fuente: Terra/AP, 9 de noviembre de 2005

Enlace: http://www.terra.com/noticias/articulo/html/act269982.htm

------------------------------------------------------

(2) Scientists unearth earliest known Hebrew ABCs

In the 10th century B.C., in the hill country south of Jerusalem, a scribe carved his ABCs on a limestone boulder - actually, his aleph-beth-gimels, for the string of letters appears to be an early rendering of the emergent Hebrew alphabet.

Archaeologists digging in July at the site, Tel Zayit, found the inscribed stone in the wall of an ancient building. After an analysis of associated pottery and the position of the wall in the layers of ruins, the discoverers concluded that this was the earliest known specimen of the Hebrew alphabet and an important benchmark in the history of writing, they said this week.

If the discoverers are right, the stone bears the oldest reliably dated example of an abecedary - the letters of the alphabet written out from beginning to end in their traditional sequence. Several scholars who have examined the inscription tend to support this view.

Experts in ancient writing said the find showed that at this stage the Hebrew alphabet was still in transition from its Phoenician roots, but recognizably Hebrew. The Phoenicians lived on the coast north of Israel, in todays Lebanon, and are considered the originators of alphabetic writing, several centuries earlier.

The discovery of the Tel Zayit stone will be reported in detail next week at conferences in Philadelphia, but was described in interviews with Ron Tappy, the archaeologist at the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, who directed the excavations.

"All successive alphabets in the ancient world, including the Greek one, derive from this ancestor at Tel Zayit," he said.

The research is supported by an anonymous donor to the Presbyterian-affiliated seminary, which has a long history in archaeological fieldwork and, Tappy said, imposed no ideological or political demands on researchers. The project is also associated with the American Schools of Oriental Research and the W.F. Albright Institute for Archaeological Research, in Jerusalem.

Frank Moore Cross Jr., a Harvard expert on early Hebrew inscriptions who was not involved in the research, said the inscription "is a very early Hebrew alphabet, maybe the earliest, and the letters I have studied are what I would expect to find in the 10th century" before Christ.

P. Kyle McCarter Jr., an authority on ancient Middle Eastern writing at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, was somewhat more cautious, describing the inscription as "a Phoenician type of alphabet that is being adapted." But he added, "I do believe it is proto-Hebrew, but I cant prove it for certain."

Lawrence Stager, an archaeologist at Harvard engaged in other excavations in Israel, said the pottery styles at the site "fit perfectly with the 10th century, which makes this an exceedingly rare inscription." But he added that more extensive radiocarbon dating would be needed to establish the sites chronology.

The Tel Zayit stone was uncovered at a more than 3-hectare, or 8-acre, site in the region of ancient Judah, south of Jerusalem, and 29 kilometers, or 18 miles, inland from Ashkelon, an ancient Philistine port.

The two lines of incised letters, apparently the 22 symbols of the Hebrew alphabet, were on one face of the stone. A bowl-shaped hollow was carved in the other side, suggesting that the stone had been a drinking vessel in cult rituals, Tappy said. The stone, he added, may have been embedded in the wall because of the ancient belief in the alphabets magical power to ward off evil.

In a close study of the alphabet, McCarter noted that the Phoenician-based letters were "beginning to show their own characteristics." The Phoenician symbol for what is the equivalent of a K is a three-stroke trident; in the transitional inscription, the right stroke is elongated, beginning to look like a backward K.

The inscription was found in the context of a substantial network of buildings at the site, which led Tappy to propose that Tel Zayit was probably an important border town established by an expanding Israelite kingdom based in Jerusalem.

A border town of such size and culture, Tappy said, suggested a centralized bureaucracy, political leadership and literacy levels that seemed to support the biblical image of the unified kingdom of David and Solomon in the 10th century B.C. "That puts us right in the middle of the squabble over whether anything important happened in Israel in that century," Stager said.

A vocal minority of scholars contend that the Bibles picture of the 10th century B.C. as a golden age in Israelite history is insupportable.

Fuente: John Noble Wilford The New York Times / Copyright © 2005 the International Herald Tribune, 9 de noviembre de 2005

Enlace: http://www.iht.com/articles/2005/11/09/news/alpha.php

*** The Pittsburgh Theological Seminary is located at 616 North Highland Ave., Pittsburgh.

Regular museum hours are 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Wednesday and 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. the first Saturday of each month.

You can visit the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary web site at www.pts.edu/museum.html for more information. You can also contact the Kelso Bible Lands Museum at 412-362-5610, extension 2278.

Jeff Pikulsky can be reached at jpikulsky@tribweb.com

Ron E. Tappy, Project Director

Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, Sponsor

616 North Highland Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15206

E-mail tappy@fyi.net Phone: 412-441-3304 x2126 Fax: 412-486-0776

The Zeitah Excavations 2000 © All Rights Reserved

http://www.zeitah.net/

1 comentario

BenYâHmín Trigueros-Muñoz -