El secreto del olivo

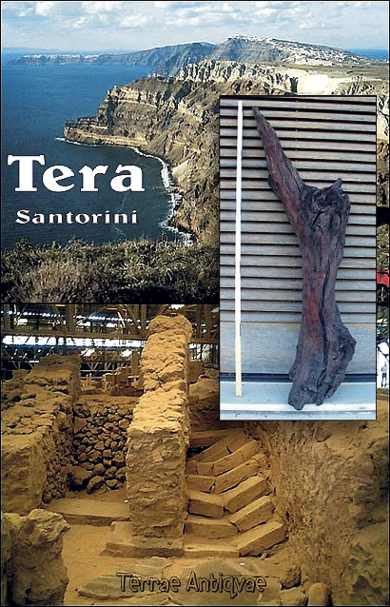

Fotos: (1) The caldera wall of Santorini. The top layer is the ash of the Thera eruption. The olive tree was found right above the head of the sitting person. (2) The olive branch, about one meter long, with the last tree ring, the bark, preserved. (3) The collapsed main staircase in Building Delta-North at Akrotiri, Santorini. - Sturt Manning- Science Magazine

Reportaje Fotográfico sobre el mundo Minoico

Fotos: José Luis Santos, Agosto 2005

Un árbol carbonizado de la isla griega de Santorini revela la fecha de la erupción volcánica más grande de la Historia

Un volcán explotó hace unos 3.500 años en la isla griega de Tera -hoy conocida como Santorini- con tal potencia que sus efectos se sintieron hasta en California y China, y olas de 12 metros se estrellaron contra las costas de Creta, a 110 kilómetros al Sur. La fecha exacta de la catástrofe es todavía objeto de debate entre los arqueólogos. Los hay que sostienen que sucedió hacia 1500 antes de Cristo (aC); otros mantienen que ocurrió entre un siglo y siglo y medio antes. Ahora, los restos de un olivo respaldan la fecha más distante, lo que obligaría a reescribir parte de la historia de la región.

La primera gran cultura europea, la minoica, se desarrolló en Creta en la Edad del Bronce, entre 2600 aC y 1400 aC. La floreciente economía de la isla se plasmó en grandes palacios como los de Festos, Hagia Triada y Cnosos, hogar del mítico rey Minos y del no menos mítico Minotauro. Esa civilización comenzó a declinar a comienzos del siglo XV aC y desapareció poco después.

Como se creía que la explosión de Tera había ocurrido en 1500 aC, durante años se especuló con la posibilidad de que estuviera en el origen del fin de los minoicos. Se argumentaba, además, que la destrucción de la cultura cretense podía haber servido de inspiración a Platón para la de la legendaria Atlántida. Sin embargo, poco a poco, fueron apareciendo pruebas de que la erupción había sucedido un siglo antes, aunque no eran tan concluyentes como las que hoy publica la revista Science.

Un equipo de la universidad danesa de Aarhus, dirigido por Walter Friedrich, descubrió hace poco en una capa de roca volcánica de Santorini una rama con corteza de un olivo carbonizado por la erupción. Los científicos usaron los restos para fijar la antigüedad del árbol mediante el método del carbono 14, y les dio como resultado que la explosión de Tera ocurrió entre 1624 aC y 1599 aC. Simultáneamente, un grupo de la Universidad de Cornell (EE UU) hizo otras dataciones de muestras de la región que sitúan la erupción entre 1660 aC y 1613 aC.

Tradicionalmente, se ha vinculado la época de mayor esplendor de la cultura minoica con el Imperio Nuevo egipcio, que empezó hacia 1550 aC con el faraón Ahmosis y alcanzó su clímax tres siglos después con Ramsés II. Si la explosión de Tera ocurrió en el siglo XVII aC y marcó el inicio del declive cretense, su auge tuvo lugar cuando los invasores hicsos todavía gobernaban Egipto.

Fuente: Science / L.A. GÁMEZ l.a.gamez@diario-elcorreo.com /BILBAO, El correo Digital, 28 de abril de 2006

Enlace: http://www.elcorreodigital.com/alava/pg060428/

prensa/noticias/Gente/200604/28/VIZ-GEN-036.html

---------------------------------------------

(2) Olive branch solves a Bronze Age mystery

By Kathleen Wren, Science

Discovery rewrites history of ancient Mediterranean civilizations

WASHINGTON - Compared to the well-studied world of Homers Iliad and Odyssey, the civilizations that flourished in the eastern Mediterranean just before Homers time are still cloaked in mystery.

Even the basic chronology of the region during this time has been heatedly debated. Now, a resolution has finally emerged -- initiated, quite literally, by an olive branch.

Scientists have discovered the remains of a single olive tree, buried alive during a massive volcanic eruption during the Late Bronze Age. A study that dates this tree, plus another study that dates a series of objects from before, during and after the eruption, now offer a new timeline for one of the earliest chapters of European civilization.

The new results suggest that the sophisticated and powerful Minoan civilization (featured in the legend of Theseus and the Minotaur) and several other pre-Homeric civilizations arose about a century earlier and lasted for longer than previously thought.

The new timeframe also downplays Egypts role in the region, suggesting that the cultures of the Levant, the stretch of land that includes Syria, Israel and Palestine, may have been a more important outside influence.

The pair of studies appears in the 28 April issue of the journal Science, published by AAAS, the nonprofit science society.

During the Late Bronze Age, large building complexes appeared on Crete and later on mainland Greece as part of the Minoan New Palace civilization. At its high point, this civilization seems to have been the dominant cultural and economic force across the region, as the result of trade rather than military strength.

On Santorini, a major prehistoric settlement called Akrotiri was buried by the Minoan eruption, preserving whats often called the Pompeii of the Aegean. Archeologists have uncovered three- and four-story houses and many other finds there, including an extraordinary collection of wall paintings that offer a glimpse into Minoan life. Women apparently played important civic and religious roles, including joining men in the sport of bull-leaping, which seems to have been religiously significant and as dangerous as the name implies.

The people of the Shaft Grave culture on mainland Greece, meanwhile, are known for burying their rulers with an eye-catching array of weapons, tools, pottery and other gold-rich ornaments. One grave contained a face mask that was originally identified as that of Agamemnon, the legendary king of Mycenae who led the Greeks against Troy in the Iliad.

The new findings suggest that it belonged to an earlier chief or king instead.

Also around the same time, major new coastal political systems were growing on Cyprus, fuelled by the islands important copper industry that supplied the metal-hungry civilizations in the east Mediterranean.

Rethinking the timeline

Its generally thought that these cultural developments in the eastern Mediterranean occurred during the 16th century B.C., along with the New Kingdom period in Egypt, when Egypt expanded its influence into western Asia.

The new studies suggests that these developments probably took place instead during the preceding Second Intermediate Period, when Egyptian power was weak and a foreign Canaanite dynasty even conquered northern Egypt for a while.

According to the new chronology, the Late Bronze Age civilizations in the Aegean and on Cyprus may have developed in association with 18th- and 17th-century Canaanite and Levantine civilizations and their expanding maritime trade world. These cultures were very different from the Egyptians in terms of culture, language and religion.

If the papers published this week in Science are correct, then a critical new historical context may explain aspects of the development, languages, literature, religion and mythology of the Aegean and the later Classical worlds, said Sturt Manning of the Cornell University and the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, who is the lead author of one of the studies.

The great debate

For more than a century, archaeologists have developed the chronology for this region by painstakingly comparing the various civilizations artifacts and artistic styles, such as how spirals were painted on pots or how metalwork was done. To pin the cultural periods to calendar dates, they then linked them to the accepted dates for the Egyptian pharaohs.

Since the 1970s, scientists have been measuring radiocarbon dates from the same areas, which dont match with this artifact-based timeframe. Because of uncertainty about the dating methods, however, the radiocarbon results havent been convincing enough to overturn the archaeologists conclusions.

Its probably the biggest controversy in eastern Mediterranean archeology, Manning said.

There has also been an inertia factor. Manning noted that if the existing chronology were wrong, it would mean rewriting the dates in museums and textbooks. And, it would have a more far-reaching effect, requiring a rethinking of some of the basic assumptions about the origins of European history.

You would have a concertina effect, since you cant move one part without upsetting the whole apple cart. Thus, it has been said that rewriting the chronology is impossible, Manning said.

The Pompeii of the Aegean

During the Minoan eruption, the volcano on what is now Santorini spewed ash and rocky debris up to hundreds of kilometers around. It was one of the largest eruptions in recorded history, and some researchers have even proposed that it was the basis for the legend of Atlantis.

The widespread volcanic ash layer offers a reference point that could potentially help line up the ages of various sites in the eastern Mediterranean, but researchers have not been able to date the layer precisely enough until now.

A remarkable solution to the problem emerged when Walter Friedrich and his graduate student Tom Pfeiffer, both of the University of Aarhus in Denmark, found the branch of an olive tree that was buried in its living position by the ash. The remains of the trees bark, leaves and twigs showed that the tree was still alive at the time of the eruption.

Ive been working on Santorini for 30 years and this is the first time I have seen such a thing, Friedrich said.

By analyzing and dating the tree rings, Friedrichs research team was able to pinpoint the age of the eruption more precisely than ever before, since the outermost ring was formed in roughly the same year that the volcano erupted.

The new timeframe for the eruption is between 1627 and 1600 B.C., a century earlier than archaeological studies have suggested.

This was one of the biggest eruptions known to mankind, and now we have a precise date for the first time, Friedrich said.

Before and after the eruption

The new age for the eruption fits in neatly with a much larger series of radiocarbon dates put together by Sturt Manning and his colleagues.

Mannings team collected a large number of seeds and some tree-ring samples from a 300-year time span that included the Minoan eruption. They put together sets of data in a known sequence from before, around, and after the eruption and used sophisticated statistical methods to define new, more precise dates than before.

Given past controversy, they took a number of precautions, such as analyzing the seeds at two separate labs, to reduce the uncertainty of the earlier radiocarbon studies. The picture now from the radiocarbon seems fairly clear, according to Manning, but in conflict with the established dates and history.

Overall, the radiocarbon results indicate that the formation and high point of the New Palace period of Crete, the wall paintings of Akrotiri, the Shaft Grave period of the Greek mainland, and the political changes on Cyprus all occurred before approximately 1600 B.C. This is not only about 100 years earlier than thought; it also implies that the overall cultural era involved lasted much longer than researchers had assumed.

The new chronology makes the world of New Palace Crete even more important and interesting, Manning said, turning the later 18th and 17th centuries B.C. into an exciting new cultural cauldron from which significant elements of European history may have originated.

Fuente: Kathleen Wren, Science / © 2006 American Association for the Advancement of Science, April 27, 2006

Enlace: http://msnbc.msn.com/id/12502996/page/2/

------------------------

By Alex Kwan

Separated in history by 100 years, the seafaring Minoans of Crete and the mercantile Canaanites of northern Egypt and the Levant (a large area of the Middle East) at the eastern end of the Mediterranean were never considered trading partners at the start of the Late Bronze Age. Until now.

Cultural links between the Aegean and Near Eastern civilizations will have to be reconsidered: A new Cornell University radiocarbon study of tree rings and seeds shows that the Santorini (or Thera) volcanic eruption, a central event in Aegean prehistory, occurred about 100 years earlier than previously thought.

The study team was led by Sturt Manning, a professor of classics and the incoming director of the Malcolm and Carolyn Wiener Laboratory for Aegean and Near Eastern Dendrochronology at Cornell. The team's findings are the cover story in the latest issue of Science (April 28).

The findings, which place the Santorini eruption in the late 17th century B.C., not 100 years later as long believed, may lead to a critical rewriting of Late Bronze Age history of Mediterranean civilizations that flourished about 3,600 years ago, Manning said.

The Santorini volcano, one of the largest eruptions in history, buried towns but left archaeological evidence in the surrounding Aegean Sea region. As a major second millennium B.C. event, the Santorini eruption has been a logical point for scientists to align Aegean and Near Eastern chronology, although the exact date of the eruption was not known.

"Santorini is the Pompeii of the prehistoric Aegean, a time capsule and a marker horizon," said Manning. "If you could date it, then you could define a whole century of archaeological work and stitch together an absolute timeline."

In pursuit of this time stamp, Manning and colleagues analyzed 127 radiocarbon measurements from short-lived samples, including tree-ring fractions and harvested seeds that were collected in Santorini, Crete, Rhodes and Turkey. Those analyses, coupled with a complex statistical analysis, allowed Manning to assign precise calendar dates to the cultural phases in the Late Bronze Age.

"At the moment, the radiocarbon method is the only direct way of dating the eruption and the associated archaeology," said Manning, who puts Santorini's eruption in or just after the range 1660 to 1613 B.C. This date contradicts conventional estimates that linked Aegean styles in trade goods found in Egypt and the Near East to Egyptian inscriptions and records, which have long placed the event at around 1500 B.C.

To resolve the discrepancy, Manning suggests realigning the Aegean and Egyptian chronologies for the period 1700-1400 B.C. Parts of the existing archaeological chronology are strong and parts are weak, Manning noted, and the radiocarbon now calls for "a critical rethinking of hypotheses that have stood for nearly a century in the mid second millennium B.C."

Aegean and Near Eastern cultures, including the Minoan, Mycenaean and Anatolian civilizations, are fundamental building blocks for Greek and European early history. The new findings stretch Aegean chronology by 100 years, a move that could mean alliances and intercultural influences that were previously thought improbable.

The new results were bolstered by a dendrochronology and radiocarbon study, led by Danish geologist Walter Friedrich and published in the same issue of Science, which dated an olive branch severed during the Santorini eruption and arrived independently at a late 17th century B.C. dating.

This work, Manning added, continues Cornell's leading role in developing a secure chronology for the Aegean and Near East headed by Professor Peter Kuniholm, who founded the Aegean Dendrochronology Project 30 years ago. "I came to Cornell in 1976 with half a suitcase of wood. Now we have an entire storeroom with some 40,000 archived pieces that cover some 7,500 years," said Kuniholm.

Fuente: Graduate student Alex Kwan is a writer intern with the Cornell News Service. Cornell University, 28 de abril de 2006

Enlace: http://www.news.cornell.edu/stories/April06/Bronze.age.AK.html

1 comentario

Angel Gomez-Moran -

Es muy interesante el hecho de poder \"volver\" a datar el final del Imperio Minoico, y situar el desastre de Tera-Santorino en el 1600 aC. (aprox). De todos modos, digo volver, ya que creo recordar que el maravilloso Sir Arthur Evans imagino hace ya cien annos que el fin de la epoca de los Palacios precisamente era en esta fecha (1600). Despues de ello, creo recordar, que en los annos 70, y tras los estudios de Angel Galanopuolos, por motivos historicos, decidieron postergar la fecha de la Caida del Minoico M. hasta 1500-1450 aC -Pues de ese modo encajaba mas en las nuevas teorias que explicaban entre otras la aparicion de nuevos Pueblos en el Mar y sobre todo la narracion del Kritias y Timaios de Platon-. No solo me alegro con la noticia el poder \"cuadrar\" mejor muchos datos historicos, sino poder conservar la memoria de personas tan superdotadas como Evans, que aun sin C-14 lo dato en la misma fecha que hoy nos dice la rama de olivo. (ruego me perdonen, pero escribo desde ordenador sin acentos ortograficos en espannol y solo con N)