Hatshepsut la reina Faraón. Exposición en El Metropolitan de Nueva York

Primera exposición de reina que se convirtió en faraona

El Metropolitan de Nueva York inaugura el martes la primera exposición que se organiza sobre Hatshepsut, la reina que se convirtió en faraona e instauró una de las épocas más doradas del antiguo Egipto.

La muestra recoge estatuas, muebles, joyas, utensilios y ajuares que proceden de varios museos y retratan a una gobernante menos conocida, pero que manejó mejor los asuntos de Estado que la más famosa de sus sucesoras, Cleopatra.

La exhibición reúne obras que prestan por primera vez el Museo Egipcio de El Cairo y el Museo de Luxor, además de piezas que la institución neoyorquina recolectó en campañas arqueológicas en las décadas de los años 1920 y 1930 en el País del Nilo.

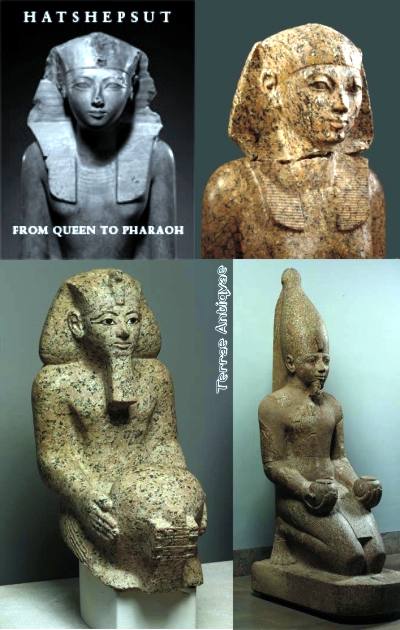

Hatshepsut aparece como reina, faraona y esfinge en inscripciones y esculturas que reflejan el esplendor de su reinado de veintiún años, de 1503 al 1482 antes de Cristo, que marcaron el inicio del renacimiento del Imperio Nuevo, del 1540 al 1070 antes de Cristo.

Su Gobierno fue tan importante para Egipto como el de Isabel I para Inglaterra, se afirma en el catálogo de la muestra, que permanecerá abierta al público hasta el 9 de julio.

No fue la primera ni la última, pero sí la más brillante reina que gobernó el Antiguo Egipto, dijo a EFE el director del Consejo Supremo de Antigüedades de Egipto, Zaki Hawas, que viajó a Nueva York para la inauguración.

Hawas, máxima autoridad arqueológica de su país, apuntó que la exposición llega en el momento perfecto para que en estos tiempos se sepa que el Antiguo Egipto fue gobernado también por mujeres, y que una de ellas se convirtió en faraona.

Hija favorita de Tutmosis I y principal esposa de Tutmosis II, Hatshepsut inicio su mandato como reina regente a la muerte de su marido y hermanastro, y después, ya como faraona, asociada al trono con su hijastro y sobrino, Tutmosis III, entonces un niño.

Durante su reinado se construyó como nunca antes en el Imperio Nuevo, se restauraron monumentos destruidos durante la invasión de los hicsos y Egipto reanudó el comercio con Oriente Medio, las Islas del Egeo y el País del Punt, en las actuales Somalia y Eritrea.

La prosperidad que propiciaron esos intercambios impulsó el arte y la arquitectura, de lo que es mayor exponente el templo funerario de Beir El Bahri, que Hatshepsut se hizo labrar en una montaña cerca del Valle de los Reyes, frente a Luxor.

En contraste con Cleopatra, que vivió 1.500 años después y ha estado siempre envuelta en la leyenda, Hatshepsut permaneció casi ignorada hasta principios del siglo XX, cuando su vida y obra comenzó a atraer el interés de estudiosos y novelistas.

La razón que le indujo a proclamarse faraona, y a vestir como un hombre y usar barba postiza, constituye, sin embargo, un enigma sobre el que los egiptólogos no se ponen de acuerdo.

La mayoría piensa que lo hizo para ganarse el respeto de su pueblo, pero no todos comparten esa opinión.

No creo que se presentara como un hombre para poder gobernar, dijo a EFE la jefa del Departamento de Egiptología del Metropolitan, Dorothea Arnold, en alusión a que, antes de Hatshepsut, reinas como Sobekneferu y Nicotris, y después la propia Cleopatra, lo hicieron sin necesidad de proclamarse faraonas.

Creo que fue algo sólo simbólico. Hatshepsut no dejó de aparecer en estatuas e inscripciones con su nombre femenino, nunca ocultó su feminidad, subrayó la especialista sobre el interés que tenía en ser recordada como una mujer de gran belleza quien ha pasado a la Historia como el quinto faraón de la décimo octava dinastía.

Una belleza que la exposición neoyorquina pone de manifiesto pese a que Tutmosis III, su sucesor y quien posiblemente la asesinó, intentó destruir todas las representaciones de Hatshepsut, e hizo lo posible por borrar su memoria.

Fuente: Terra Actualidad EFE, 27 de marzo de 2006

Enlace: http://actualidad.terra.es/cultura/articulo/

exposicion_reina_convirtio_faraona_803240.htm

-----------------------------------

(2) Hatshepsut mummy found

The true mummy of ancient Egyptian queen Hatshepsut was discovered in the third floor of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Secretary General of Supreme Council for Antiquities Zahi Hawwas revealed on Thursday.

The mummy was missing among thousands of artifacts lying in the museum, he said during his lecture at the New York-based Metropolitan Museum of Arts.

He said for decades archaeologists believed that a mummy found in Luxor was that of the Egyptian queen. It was a streak of luck, he said, to find this mummy.

The Metropolitan is hosting a Hatshepsut exhibition that displays 270 artifacts on the life history of the queen.

The American museum honoured Hawwas and his accompanying delegation in appreciation of their effort to unravel the mysteries of the Egyptian Pharaohnic age.

Fuente: ©Egypt State Information Service 2005, 24 de marzo de 2006

Enlace: http://www.sis.gov.eg/En/EgyptOnline/Culture/

000001/0203000000000000000593.htm

------------------------------------------

(3) Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh

Special Exhibition Galleries, The Tisch Galleries, 2nd floor

Hatshepsut, the great female pharaoh of Egypts 18th Dynasty, ruled for two decadesfirst as regent for, then as co-ruler with, her nephew Thutmose III (ca. 14791458 B.C.). During her reign, at the beginning of the New Kingdom, trade relations were being reestablished with western Asia to the east and were extended to the land of Punt far to the south as well as to the Aegean Islands in the north.

The prosperity of this time was reflected in the art, which is marked by innovations in sculpture, decorative arts, and such architectural marvels as Hatshepsuts mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. In this exhibition, the Metropolitans own extensive holdings of objects excavated by the Museums Egyptian Expedition in the 1920s and 1930s will be supplemented by loans from other American and European museums, as well as by select loans from Cairo.

The exhibition is made possible by Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman.

The exhibition catalogue is made possible by The Adelaide Milton de Groot Fund at the Metropolitan Museum, in memory of the de Groot and Hawley families.

It was organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities, and by generous grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the National Endowment for the Arts, Federal agencies.

Fuente: Copyright © 20002006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, March 28, 2006July 9, 2006

Enlace: http://www.metmuseum.org/special/se_event.asp?

OccurrenceId={92C8F718-137B-4AE6-9FAA-C8DA6CCE72CC}

----------------------------------------

(4) Our pharaoh lady

A Met exhibit delineates a queens rise in molding herself as Egypts king

BY ARIELLA BUDICK

Newsday Staff Writer

March 26, 2006

The 18th Dynasty pharaoh Hatshepsut surely wins the prize for gutsiest cross-dresser of all time, if only because she played for the highest stakes. Hatshepsut ruled Egypt for two decades (from 1479 to 1458 BC), which makes her the first major female head of state - the first one we know about, anyway. While women could be leaders in ancient Egypt, a pharaoh was by definition male. So Hatshepsut had to invent a hybrid gender, presenting a challenge to the sculptors charged with translating her flesh into stone.

Hatshepsuts fluid identity is the focus of a captivating and opportune exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum that focuses both on the fruitful period of her reign and on shifting representations of the woman herself.

The daughter of one pharaoh, and queen to another, Hatshepsut ruled after her husbands death, acting as regent for a stepson. Up to that point, her trajectory was not unusual. Women had ruled Egypt before as "mothers of the king," keeping the dynasty intact while their young charges matured.

But while these caretaker queens were expected to step aside when the child came of age, Hatshepsut moved quickly to have herself definitively crowned. She didnt officially depose the boy, but ruled alongside him as senior co-pharaoh.

No one knows what drove her to this radical move, but it could never be reversed; pharaohs were gods and could not renounce their divinity. Hatshepsuts reign initiated an artistic flowering accompanied by stability, peace and prosperity.

The female king

Her transition from human queen to godly king can be tracked through changing representations of her body. One exquisite statue depicts her as a "Female King": The long, slender torso, delicate limbs and small, round breasts leave no room for doubt about her sex. Nor does the distinctive triangular face with its broad, high cheekbones, hooded eyes, narrow mouth and pointy little chin.

What sets the figure apart from other portraits of female royalty is the nemes (a head cloth worn only by male rulers) draped around her face. Beneath it, the pharaohs piercing gaze indicates extreme self-possession and a propensity for power.

She adopts a nearly identical pose in "Hatshepsut as King," but in a gorgeous embodiment of ambiguous eroticism, she wears a mans clothes and inhabits a body that looks more like an adolescent boys - except for the sprouting breasts. We recognize the face: heart-shaped and wide across the cheeks, tapered at the chin.

Instead of a thin sheath, the topless Hatshepsut wears a pleated kilt, beaded belt and a bulls tail between her legs, all emblems of male royalty. Yet the identifying inscription down the front of the throne makes clear that this is no man: "The Perfect Goddess, Lady of the Two Lands ... May she live forever!"

She has, in a way. Her heirs were all female potentates, from Englands fiercely sexless queens, Elizabeth I, Victoria and Elizabeth II, to the iron-fisted Indira Gandhi, the tough Golda Meir, the iron-plated Margaret Thatcher and this countrys power-suited senators. Women who lead wear neutralizing armor and present a scrupulously masculinized image.

The most extreme sculptures portray Hatshepsut as unequivocally male. In two of the biggest, from the mortuary temple she built at Deir el-Bahri in western Thebes (opposite modern Luxor), she kneels, holding a globular vessel in each hand. These colosssi have much more generic facial features than the earlier royal portraits. The idiosyncratic, catlike face has become blanker and more idealized; the willowy body has grown meaty and thick.

The pharaohs calf muscles strain against her heavy thighs and her toes splay out gracelessly. The narrow, swelling chest of a queen has turned into the broad muscular barrel of a king. Her reassignment is complete.

Royal defacement

Hatshepsuts death occasioned no rupture in the orderly succession of power. The boy king Thutmose III had grown up and continued to govern on his own. Yet 20 years later, something snapped, and he initiated a rabid attack on Hatshepsuts legacy. His minions pulverized her monuments, hacked her name from inscriptions, and erased her image from temple walls. Subsequent Egyptian king lists omitted her name.

Hatshepsut lay buried until 1906, when the Metropolitan Museums team began to excavate at Thebes. Led by Egyptologist Herbert Winlock, they discovered thousands of fragents in an ancient quarry, which they painstakingly reassembled into a multifaceted portrait of a forgotten monarch.

The posthumous spasm of violence against her is one of the great Freudian mysteries of antiquity. Or perhaps not, for when in our modern experience has a woman acquired power without fomenting an equally potent backlash?

WHEN & WHERE

"Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharoah. " Opens Tuesday, on view through July 9 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Ave. at 82nd Street, Manhattan. For exhibition hours and admission prices call 212-535-7710 or visit www.metmuseum.org.

Fuente: http://www.newsday.com/entertainment/arts/

ny-ffart4672114mar26,0,1974262.story?coll=ny-arts-print

1 comentario

jhony fabian arroyave aljak -