Perú demandará a Yale para recuperar piezas de Machu Picchu

NUEVA YORK (Reuters) - Perú demandará a la Universidad de Yale para recuperar miles de piezas arqueológicas que fueron extraídas de Machu Picchu hace más de 90 años, luego de que las negociaciones se rompieran y las partes se acusaran mutuamente esta semana de actuar de mala fe.

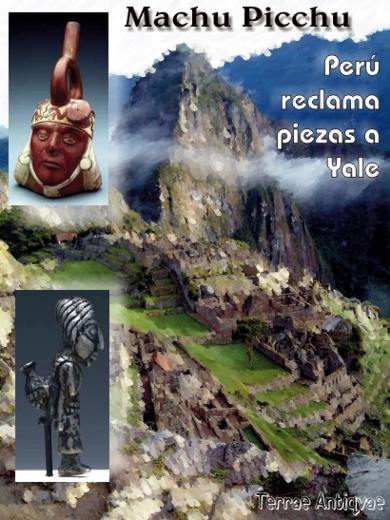

Fotos de la colección de la Galería de Arte de la Universidad de YALE:

(1) Stirrup-spout vessel with human portrait

Moche, North Coast, Peru, ca. A.D. 200550

Ceramic, 11 5/16 in. (28.7 cm) high

University Purchase

1956.27.7

The Moche culture, which dominated the north coast of Peru for most of the first 500 years A.D., developed a "corporate" artistic style unifying disparate elements of the various cultural groups incorporated, often by force, into Perus earliest empire. Among the chief characteristics of Moche art is an emphasis on individual rulers and warlords, which stimulated the development of a tradition of portraiture. The head that serves as the main element of this painted stirrup-spout bottle probably portrays a local ruler or the head of a clan. Many such "portrait" vessels are known, and the specificity of the facial features and costume attributes suggests that each was meant to represent a different individual. The bottles stirrup spout was designed to prevent spillage and evaporation of the liquids contained within.

(2) Woman carrying a water jar

Inca, Peru, ca. A.D. 14351534

Silver, 1 3/4 in. (4.5 cm) high

Gift of Thomas T. Solley, B.A. 1950

2002.15.7

The metallurgical arts achieved a high level of sophistication under the Inca, who came to control the whole of Peru for almost a century prior to the Spanish conquest of the region. This tiny figurine of solid silver depicts a woman carrying an olla (water jar) on her back. The jar is attached to her by means of a rope, one end of which wraps around her waist and the other around her neck, where she grasps it with her hands. Her lowered head and slightly forward shoulders create the impression of a weary figure carrying a heavy load. At the top and back of the womans head are two small holes that would have allowed the figurine to be strung as a pendant or attached as an ornament.

Perú busca la devolución de unos 4.900 objetos de la ciudadela incaica, entre los que se encuentran cerámicas, ropa y orfebrería. El país andino dice que las piezas fueron prestadas a Yale por 18 meses en 1916, pero la universidad estadounidense las ha tenido desde entonces.

"Yale no reconoce que el Estado peruano es dueño de estas piezas," dijo el embajador de Perú en Washington, Eduardo Ferrero, en un comunicado.

Ferrero lamentó que después de tres años de conversaciones, las autoridades de Yale no hayan actuado conforme al "principio de buena fe."

En su comunicado reseña que el explorador Hiram Bingham fue autorizado a exportar las piezas bajo el supuesto de que iban en calidad de préstamo y que serían devueltas.

Por su parte, Yale dijo en otro comunicado enviado el jueves a Reuters que la semana pasada presentó una propuesta alternativa que incluía el retorno de varios objetos.

"Estamos decepcionados porque el gobierno (peruano) ha desestimado esta propuesta y aparentemente está decidido a demandar a la Universidad de Yale," afirmó.

La universidad refirió que la colección fue legalmente excavada y exportada "de acuerdo a las prácticas de la época."

"Lamentamos que el gobierno peruano haya roto las negociaciones antes de las elecciones, en lugar de trabajar un marco para una resolución estable y de largo plazo," acotó.

Perú realizará elecciones generales el 9 de abril.

En el comunicado, la universidad dijo que propuso trabajar con el gobierno peruano para establecer exposiciones paralelas de los objetos en Yale y en un nuevo museo que será construido en Perú.

Perú busca recuperar las piezas arqueológicas porque quiere exhibirlas en el 2011, cuando se conmemorará el centenario del descubrimiento de Machu Picchu por Bingham.

El embajador de Perú dijo que la última oferta de Yale era inaceptable porque no reconoce que el país andino es dueño de los objetos.

"(Yale) sostiene que estas piezas arqueológicas pertenecen a la humanidad, pero al mismo tiempo pretende apropiarse de parte de la colección," señaló Ferrero.

"El gobierno de Perú (...) presentará una demanda contra la Universidad de Yale ante los tribunales de Estados Unidos," agregó el embajador.

Bingham descubrió en 1911 Machu Picchu en los andes sureños de Perú, en medio de una zona montañosa.

Las ruinas precolombinas estuvieron olvidadas bajo la selva húmeda a unos 2.500 metros sobre el nivel del mar, cerca de la ciudad de Cuzco, capital del imperio incaico.

Machu Picchu fue el corazón del imperio incaico, que dominó América del Sur de Colombia a Chile hasta que llegaron los conquistadores españoles en 1532.

La ciudadela atrae a medio millón de turistas cada año.

Fuente: Claudia Parsons / © Reuters - América Latina, 2 de marzo de 2006

Enlace: http://lta.today.reuters.com/news/newsArticle.

aspx?type=domesticNews&storyID=2006-03-02T230336Z

_01_N02717450_RTRIDST_0_LATINOAMERICA-PERU-EEUU-YALE-SOL.XML

-----------------------

(2) "El Perú es el único dueño de las piezas de Machu Picchu retenidas ilegalmente por la universidad de Yale"

El Embajador del Perú en los Estados Unidos de América, Eduardo Ferrero, respondió a la nota de prensa publicada esta tarde por la Universidad de Yale respecto a las negociaciones entre la Universidad de Yale y el Gobierno del Perú.

"Es desafortunado que después de más de 3 años de conversaciones, Richard Levin, Presidente de la Universidad de Yale y Dorothy Robinson, Vicepresidenta y Asesora Jurídica de dicha Universidad, no hayan actuado conforme al principio de buena fe.

El Gobierno del Perú, aún cuando es propietario de las piezas arqueológicas que Hiram Bingham llevó a Yale, siempre ha buscado un diálogo constructivo con las autoridades de dicha universidad para llegar a un acuerdo mutuamente beneficioso.

Las autoridades de Yale quieren sorprender a la opinión pública y han retrocedido en sus propuestas en relación a los constantes esfuerzos del Gobierno del Perú en los últimos años para resolver la situación de las piezas arqueológicas entregadas expresamente en préstamo por el Perú a Bingham durante las expediciones de Yale- National Geographic entre 1911 y 1915.

Yale intenta definir su propuesta como si se tratase de una división igualitaria de piezas arqueológicas para dos museos, lo que es inaceptable. Yale no reconoce la propiedad del Estado peruano sobre esas piezas. Además, sostiene que estas piezas arqueológicas pertenecen a la humanidad, pero al mismo tiempo pretende apropiarse de parte de la colección.

Desde hace años, en el inicio de las negociaciones para recuperar estas piezas arqueológicas, nuestro país ha estado dispuesto a otorgar en préstamo parte de la colección de Machu Picchu traída por Bingham a los Estados Unidos, conforme a la ley peruana, pero siempre y cuando Yale reconozca la propiedad peruana de estos tesoros y la obligación de que sean devueltos a nuestro país.

Este es un caso especial, pues Bingham se llevó las piezas arqueológicas del Perú con la autorización legal correspondiente y en el entendimiento expreso de que todas estas piezas fueron otorgadas en préstamo para luego ser devueltas al Perú. Han pasado casi 90 años y Yale aún no ha cumplido con devolver este patrimonio al Perú.

La National Geographic Society, quien se asoció con Yale en tres de las expediciones de Bingham al Perú, y ha publicado relatos específicos sobre las expediciones en la Revista National Geographic , dijo hace poco que "la National Geographic Society ha revisado sus archivos y le ha entregado tanto a la Universidad de Yale como al Gobierno del Perú, los documentos pertinentes que se encuentran en nuestra posesión en relación a las expediciones conjuntas de Yale-Hiram Bingham-National Geographic. La opinión de esta institución, previamente entregada a ambas partes, es que las piezas arqueológicas excavadas en el Perú durante estas expediciones conjuntas fueron un préstamo, pertenecen al Perú, y deben ser devueltas al Perú".

El Gobierno del Perú está sorprendido por la posición tomada por las autoridades de esa prestigiosa universidad y presentará una demanda contra la Universidad de Yale ante los tribunales de los Estados Unidos.

Washington D.C. 1 de marzo de 2006"

Lima, 2 de marzo de 2006

MINISTERIO DE RELACIONES EXTERIORES

Fuente: El Comercio, Perú, 2 de marzo de 2006

Enlace: http://www.elcomercioperu.com.pe/EdicionOnline/Html/2006-03-02/onlPortada0465513.html

-----------------

Sitios relacionados:

http://artgallery.yale.edu/

http://artgallery.yale.edu/

pages/collection/permanent/pc_artamericas.html

http://www.peabody.yale.edu//exhibits/machupicchu.html#exhibit

http://www.peru-machu-picchu.com/map.php

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Machu_Picchu

--------------------------

Who owns Inca treasures?

Peru may sue Yale for the return of Incan artifacts from Machu Picchu, many of which are part of an exhibit about the Incas and their majestic city.

WASHINGTON That day dawned unpromising, cold and drizzly, in the jungle foothills of Peru 95 years ago. The guides wanted to sleep in, but the explorer insisted on pressing deeper into the land of the Inca.

Which way are the ruins? demanded Hiram Bingham, a product of Yale in a battered gray fedora. The guide pointed straight up the mountain.

They climbed more than 2,000 feet along narrow paths, dodging poisonous snakes, inching across slippery logs spanning a raging river.

They rounded a promontory and the stunned explorer beheld his future and humanitys past.

"It fairly took my breath away," he recalled later. "What could this place be?"

It was Machu Picchu, a lost city in the clouds, a terraced and cut-stone wonder that ranks somewhere with the Pyramids among examples of ancient technological prowess.

It is the pride of modern Peru, a major tourist attraction and subject of a bitter dispute that erupted this month between Yale and Peru over who owns hundreds of artifacts Bingham collected during three expeditions. Many of those objects bones, pottery, tools reside at the Yale Peabody Museum.

Peru wants the objects back; Yale wants to keep them.

Alejandro Toledo, the first indigenous president of Peru, is scheduled to meet today with the Yale graduate who inhabits the White House as part of a visit promoting democracy and trade.

The Machu Picchu artifacts are not on the official agenda, but Toledo will likely raise the topic with President Bush, said Peruvian embassy sources, even though he considers the dispute a matter between his government and Yale, not between Peru and the United States. The White House agrees.

Two weeks ago, Yale proposed returning many of the artifacts but insisted on retaining a large number to ensure that "research and scholarship of these objects will continue." Peru insisted that Yale recognize Peruvian ownership of all the artifacts but suggested that some could remain on loan at the Peabody.

Peruvian Ambassador Eduardo Ferrero charged last week that Yale has "not acted in accordance with the principles of good faith," and he threatened a lawsuit. The university, meanwhile, asserted that Peru had "broken off negotiations ... instead of working out the framework for a stable and long-term resolution."

The biggest blow to Yales case came last week when the National Geographic Society which co-sponsored with Yale two of Binghams expeditions and whose chairman, Gilbert M. Grosvenor, is a Yale graduate concluded the artifacts belong to Peru and called for their return.

Even though this case comes amid a rising tide of seemingly similar disputes and settlements the Metropolitan Museum of Art last month agreed to return looted works to Italy in exchange for loaned art, while the British Museum holds on to the Elgin Marbles its documentary record makes it unique.

Ferrero calls Bingham a " rediscoverer, not discoverer because Machu Picchu was already known by people" in the area, he says. Dating to the 15th century and abandoned sometime in the 16th, the city was an elaborate vacation retreat for Incan nobility. Its discovery enhanced modern understanding of a sophisticated civilization that existed long before Spanish invaders overran the territory.

Seated in his office on Embassy Row, the ambassador leafs through pages of records photocopies of Peruvian decrees passed in 1912 and 1914 to regulate Binghams expeditions, letters on Yale stationery from Bingham to Gilbert H. Grosvenor, then-president of National Geographic.

He reads aloud from a Bingham letter dated Nov. 28, 1916: "Now they" the artifacts from the third expedition "do not belong to us, but to the Peruvian government, who allowed us to take them out of the country on condition that they be returned in eighteen months."

Yale contends that under an 1852 law it is not obligated to return material collected on the first two expeditions. But Peru cites a 1912 decree in which it "reserves its right to request" return of any artifacts Bingham might find, or had found.

Fuente: By David Montgomery, The Washington Post

Copyright © 2006 The Seattle Times Company, 10 de marzo de 2006

Enlace: http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/

html/nationworld/2002855658_machu10.html

--------------------------------------

(2) An Ancient Cultural Claim

Hartford Courant

March 10, 2006

After slashing his way through jungle, Hiram Bingham reached a remote ridge high in the Andean mountains. There, shrouded in clouds, lay a captivating sight: the stone ruins of Machu Picchu, one of the Incas ancient "lost" cities.

Binghams find in 1911 in Peru came as scientists and treasure seekers alike were scouring the globe for discoveries. On two later expeditions, Bingham dug up more than a hundred tombs on Machu Picchu and shipped back crate loads of skeletons, ceramics, shawl pins and other jewelry to Yale, where he was a professor. Bingham persuaded Peru to let him borrow the antiquities and Peru drafted two "executive decrees" to make sure it all came back.

Not all of it did.

For more than three years, Peru has negotiated quietly with Yale University over the repatriation of its artifacts. But now the dispute has spilled into the open, with Peru denouncing the Ivy League institution, and the National Geographic Society - which helped fund Binghams expeditions - adding a powerful voice in support of Peru. President Bush, a Yale graduate, meets with Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo today at the White House, where the question of Perus Machu Picchu relics is bound to come up.

The dispute is unlike those that have arisen over looted artifacts. The Metropolitan Museum of Art recently agreed to give Italy back its Euphronios krater vase, which had been robbed from an Etruscan tomb and later sold. The Machu Picchu relics were never plundered. Peru says Bingham simply borrowed them and failed to give them all back. Some of the items - from ceramic jars for carrying corn beer to polished mortars and pestles for grinding herbs - are on display in a show titled "Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas," at Yales Peabody Museum. Yale has repeatedly offered to share the material and show it jointly with Peru. But Yale has refused to acknowledge Peru has full title to the artifacts - and Peru will settle for nothing less.

Peru now has the backing of the National Geographic Society, which is worried that the flap might tarnish its good name and jeopardize its reputation in parts of the world still resentful over the legacy of Europes colonial empires. "We felt a legal and moral obligation to comply with what we originally agreed to, when we went into Peru," said Terry Garcia, who oversees National Geographic expeditions. "After a lot of research by our lawyers in house and two firms on the outside we all concluded that on the face of it, Peruvian law required the objects to be returned." Bingham referenced the loan agreements in dozens of letters sent to National Geographic and Yale. In them, he complained about delays in shipping scores of boxes as World War I raged. He also expressed disdain for Perus vigilance in guarding its patrimony. "A lot of the material is duplicate material for which they could have no possible use and which will merely be thrown into their cellars or out into the street, and they know it," he wrote to National Geographics chairman, Gilbert H. Grosvenor, in 1916. "This decree is merely a sop to the multitude to show the people how careful the politicians are of their archaeological treasures."

If Peru follows through on its threat to sue, the letter may well become "Exhibit A" on its list of evidence. A prominent Washington, D.C., law firm, Williams & Connolly, has taken the case. The lawyer on it, Greg Craig, is a Yale Law School graduate and grandson of another Yalie who led Binghams mules on one expedition.

"All artifacts taken from Machu Picchu belong as a matter of law to Peru," said Craig. "Its part of their identity, who they are, where they came from." Yale says it returned most of the artifacts long ago and has justified its ownership to the rest under Perus Civil Code of 1852. The university estimates it has 250 museum-quality pieces and that most of the other artifacts have value to researchers only. That may not matter to Peruvians, who regard Machu Picchu as a symbol of national pride and the great Inca civilization that fell to Spanish conquerors in 1532.

"Machu Picchu is the most important ruin in Peru," said Esther Pasztory, an art history professor at Columbia University. "Anything from Machu Picchu has a certain resonance." It was atop Machu Picchu that Perus first native president, Alejandro Toledo, chose to give his inaugural address, in 2001. Though Toledo has made the retrieval of Perus cultural patrimony a priority, Peruvians were agitating for Yale to return the artifacts even before Toledo took office, said Garcia, at National Geographic. Yale "had an opportunity to do the right thing and be a leader and show the world how you handle issues like this. They failed," he said. "Someone didnt take `Law and P.R. 101" In photographs taken at Machu Picchu, a fedora is pulled over Binghams brow. Young and handsome, he looks as if he had walked off the set of "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom." Yales exhibit captures the romance and heady thrill of those days. A letter from Kodak founder George Eastman congratulates Bingham on his find. An invoice from outfitter Abercrombie & Fitch lays out the provisions: sugar, prunes, tea, and two leather strips to make hinges for closing the food container, in a time before Tupperware. Despite his enthusiasm, Bingham was untrained in archaeology and bungled the excavations, scientifically speaking. His theories about Machu Picchu all proved wrong, including his hypothesis that it had served as a spot for sacrificing virgins. Yet, his best-selling memoir, "Lost City of the Incas," helped put Machu Picchu on the map and the artifacts he schlepped home sparked many of the breakthroughs made in recent years. Machu Picchu is now thought to have been a vacation retreat for Incan royalty. "For almost a hundred years the Peabody was the place people went to if they wanted to learn about Peruvian culture," said Binghams grandson, David, a gynecologist living in Salem. "Peru got a huge bonus: Most of it would have been lost or poorly taken care of." Peruvians have heard the argument, and its patronizing implication, before. Garcia said plenty of good research is now being done in Peru. This week, Perus ambassador to the United States, Eduardo Ferrero, broke his silence. "Yale has a legal and moral obligation to return these objects to Peru," he asserted. "Its a very bad example to set for students to keep things that dont belong to them."

A discussion of this story with Courant Staff Writer Kim Martineau is scheduled on New England Cable News each hour today between 9 a.m. and noon.

Fuente: http://www.topix.net/content/trb/

0970100516305439784516733406990738879485

9 comentarios

cesar -

cesar -

alfaro odicio g -

eso solo tienen un nombre ¡ladrones ,aprobechados!... ¿a esa universidad mandan a sus hijos?

beni -

Alex -

Nuestra cultura Inca fue una sin igual en todo el mundo, y sus artefactos y vestigios representan nuestro pasado, así como también forma parte de nuestro presente y porvenir, por que su sola existencia nos hace entender nuestra importancia como cultura y como seres humanos.

Edgard -

Se trata de una cuestión de principios con arreglo al Estado de Derecho que toda sociedad civilizada debe respetar con gran celo.

Por otra parte, pero en el mismo camino, sugiero que visiten la Página Web porladignidaddemachupicchu.blogspot.com ahí encontrarán una iniciativa civil a través de la Internet que tiene por finalidad tender una una gran red de solidaridad a favor del pedido del Perú.

Gracias.

Sergio Alonso -

malaga_sergio13@hotmail.com

Esperando su respuesta

Pool Zorrilla Cordova -

Alexander -

Y es lamentable la posición adoptada por esta prestigiosa universidad.

El Perú es un país con un pasado maravilloso, lleno de cultura, con un pasado milenario, y paisajes majestuosos como los de la ciudadela de Machupicchu, donde la cultura Inca y preinca son fuente de conocimiento e inspiración para quien logre conocer este país. La cultura brota por sus selvas, montañas y costas.

Talvez en EEUU no se logre ver esta expresión de cultura. Sino la cultura de las destrucción de otras sociedades, que es una práctica no casi, sino terroista, que hacen estas torpezas que son tan evidentes.

Es así que se espera la devolución de los restos Incas y que estos sean exhibidos en su lugar de origen, o sea en un museo Peruano.