El amanecer de la guerra. Un equipo de arqueólogos descubre en Siria los restos de una gran batalla de hace 5.500 años

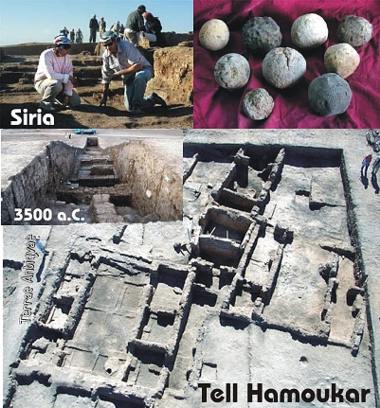

Fotos: (1) Imagen de las excavaciones en Tell Hamoukar, en Siria. (2) Algunas de las 1.320 balas de barro encontradas. (UNIVERSIDAD DE CHICAGO) (3) This photo aerial provided by the University of Chicago taken on Oct. 25, 2005, shows the Hamoukar excavation on the upper edges of the Tigris and Euphrates Valleys, near the Iraq border that an archaeological team says may have been settled as long as 8,000 years ago. Researchers from the University of Chicago and the Department of Antiquities in Syria, in a joint announcement Thursday, Dec. 15, 2005, said they had uncovered a sophisticated ancient settlement, suddenly wiped out by invaders 5,500 years ago, which they describe as the oldest known excavated site of large-scale organized warfare.(AP Photo/The University of Chicago) (AP)

Una ciudad cualquiera de Oriente Próximo. Un ejército amenazador que avanza desde el sur. Un asalto que empieza con una terrible lluvia de miles de proyectiles. Terror, gritos, sangre.

La descripción evoca escenarios familiares -hasta habituales hoy día- que casi no serían noticia si las balas en cuestión no fueran de barro y el choque no se remontara al año 3.500 antes de Cristo. Es decir, si no se tratara de la batalla más antigua que se conoce, según opinan los arqueólogos de la Universidad de Chicago y del Departamento de Arqueología sirio que llevan las excavaciones en el sitio de Tell Hamoukar, en el noreste del país asiático, casi en la frontera con Irak.

"Lo que pasó allí no fue una escaramuza. Aquello fue el Shock and awe (Choque y pavor), el nombre de la campaña militar estadounidense lanzada en 2003 para derrumbar el régimen de Sadam Husein) del cuarto milenio antes de Cristo", dice Clemens Reichel, co-director del equipo. El derrumbe de las murallas, las 1.320 balas y proyectiles encontrados hasta ahora y las evidencias de incendios inducen a pensarlo.

"Todos los elementos que tenemos a disposición convergen en indicar que Tell Hamoukar fue asediada", explica Reichel en una conversación telefónica desde Chicago. "Y la hipótesis más sólida es que los atacantes fueron soldados de un ejército del sur de la antigua Mesopotamia. Por lo menos fueron poblaciones del sur, de la civilización Uruk, las que ocuparon la ciudad tras su caída", prosigue.

Los hallazgos del equipo de Reichel -recogidos por la prensa norteamericana en estos días- apuntan entonces a que ya en esa época había estructuras militares lo suficientemente organizadas como para coordinar una expedición con centenares de hombres, con miles de municiones y con catapultas, desde distancias notables. Uruk, el centro pujante de la civilización de la Mesopotamia del sur, distaba centenares de kilómetros de Tell Hamoukar. Y aunque la expedición fuera organizada desde otro centro más cercano, en todo caso demostraría una sorprendente capacidad logística.

"El descubrimiento es interesante. Balas parecidas a las de Tell Hamoukar se han hallado ya en otros lugares. Pero nunca en esa cantidad y, sobre todo, en esa fecha", comenta Carmen Valdés, arqueóloga del Instituto de Oriente Próximo Antiguo de la Universidad de Barcelona.

"Es un periodo importante para Mesopotamia, que en ese momento albergaba las culturas más desarrolladas del planeta", prosigue la arqueóloga, que cuenta con muchos años de excavaciones en Siria. "En Europa, entonces, estábamos todavía en el neolítico final, vivíamos en cuevas, empezaban los primeros pequeños asentamientos. Pero en Mesopotamia es plausible pensar que ya existiera la capacidad de organizar un asalto militar de ese tipo. Lo que pasa es que hasta ahora no me consta que se hubieran hallado pruebas".

Además de todo eso, el interés de Tell Hamoukar reside también en que refuerza "la idea de un desarrollo de las realidades urbanas del norte de Mesopotamia autónomo, y no sólo fruto de la actividad colonial de Uruk, como se pensaba hasta hace un tiempo", argumenta Reichel. "No encontramos señales de la presencia o influencia sureña antes del ataque. La ciudad probablemente se formó como centro de comercio y de elaboración de materiales y metales, como punto intermedio entre la Anatolia rica de recursos naturales y la Mesopotamia del sur rica y pujante económica y socialmente, pero pobre en materias primas. Nosotros pensamos que llegó a tener casi 2.000 habitantes, una cifra elevada por aquellos tiempos, aunque es difícil estar seguros de ello".

Fue allí que llegó la devastadora lluvia de fuego y balas hallada por Reichel y su equipo. La primera batalla de la que se tiene conocimiento. La primera de una larga serie de violencias motivadas por el control de las materias primas.

Pompeya, en Mesopotamia

La Mesopotamia y el cuarto milenio antes de Cristo son un espacio y un tiempo de afirmación de la ciudad. Las excavaciones de Tell Hamoukar representan una fotografía interesante. "La guerra a veces es un factor positivo para los arqueólogos", explica Clemens Reichel, codirector del equipo que trabaja en la ciudad siria. "En este caso lo fue porque el ataque sorprendió a la población, y los edificios derrumbados mantuvieron en el interior todo lo que sus habitantes utilizaban para vivir. Todo se quedó congelado. Y aunque encima de las ruinas los vencedores edificaran nuevas estructuras, lo que se mantuvo por debajo permaneció allí. Y hoy, volviendo a la luz, refleja la dinámica de especialización de las actividades que es el alma de la ciudad. Los ciudadanos ya no tienen que preocuparse de la subsistencia, y pueden dedicarse a otras cosas... a especializarse".

Sólo una parte de Tell Hamoukar -1,5 hectáreas- ha sido excavada. Reichel espera poder volver allí en 2006. "Todo permaneció allí sepultado durante milenios. Como si nos estuviera esperando". Como si se tratara de una pequeña Pompeya mesopotámica.

Fuente: ANDREA RIZZI / El País.es, 26 de diciembre de 2005

Enlace: http://www.elpais.es/articulo/elpporcul/

20051226elpepicul_3/Tes/amanecer/guerra#DESPIECE_1

----------------------------

(2) Ancient Civilization Unearthed in Syria

CHICAGO -- An excavation project on the Syrian-Iraqi border has uncovered an ancient settlement wiped out by invaders 5,500 years ago.

Discovered in northeastern Syria, the ruined city of Hamoukar appears to have been a large city by 4,500 B.C., said archaeologists Clemens Reichel and Salam al-Quntar, who co-directed Syrian-American excavations on the site.

Reichel, a research associate at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, and al-Quntar, of the Syrian Department of Antiquities, jointly announced their discoveries on Thursday.

They said Hamoukar was a flourishing urban center at a time when cities were thought to be relegated hundreds of miles to the south.

The site is in the upper edges of the Tigris and Euphrates Valleys, near the Iraq border. Reichel said it may have been settled as long as 8,000 years ago.

Scholars had long believed that urbanized societies started and were isolated in Uruk, in southern Mesopotamia. But excavations that started in 1999 at Hamoukar and at other sites in central Syria led to new ideas about the how urban culture spread in the region. Ancient Mesopotamia was a region that includes Iraq and parts of Syria.

This year, the Syrian-American excavations discovered evidence of the battle that toppled and burned Hamoukar's walls and ended the city's independence. Researchers found that invaders likely hurled more than 1,200 sling-fired bullets at Hamoukar and more than 100 heavy, 4-inch clay balls.

"The whole area of our most recent excavation was a war zone," Reichel said.

The ruins have preserved not only local pottery and artifacts, but also vast amounts of Uruk pottery.

"The picture is compelling," Reichel said. "If the Uruk people weren't the ones firing the sling bullets, they certainly benefited from it. They took over this place right after its destruction."

Reichel said if Hamoukar's residents were taken by surprise it will give researchers plenty to study because their possessions likely were buried with them under the debris.

Fuente: The Associated Press / © Copyright 1996-2005 The Washington Post Company, 16 de diciembre de 2005

Enlace: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/

article/2005/12/16/AR2005121601613.html

----------------------------

(3) Earliest evidence for large scale organized warfare in the Mesopotamian world

University of Chicago-Syrian team report on work near the Iraqi border.

A huge battle destroyed one of the world's earliest cities at around 3500 B.C. and left behind, preserved in their places, artifacts from daily life in an urban settlement in upper Mesopotamia, according to a joint announcement from the University of Chicago and the Department of Antiquities in Syria.

"The whole area of our most recent excavation was a war zone," said Clemens Reichel, Research Associate at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Reichel, the American co-director of the Syrian-American Archaeological Expedition to Hamoukar, lead a team that spent October and November at the site. Salam al-Quntar of the Syrian Department of Antiquities and Cambridge University was Syrian co-director. Hamoukar is an ancient site in extreme northeastern Syria near the Iraqi border.

The discovery provides the earliest evidence for large scale organized warfare in the Mesopotamian world, the team said.

The team found extensive destruction with collapsed walls, which had undergone heavy bombardment by sling bullets and eventually collapsed in an ensuing fire. Work during an earlier season showed the settlement was protected by a 10-foot high mud-brick wall.

The excavators retrieved more than 1,200 smaller, oval-shaped bullets (about an inch long and an inch and a half in diameter) and some 120 larger round clay balls (two and half to four inches in diameter). "This clearly was no minor skirmish. This was 'Shock and Awe' in the Fourth Millennium B.C.," Reichel said.

Excavations at Hamoukar have played an important role in redefining scholar's understanding of the development of civilization. Earlier work had contended that cities first developed in the lower reaches of the Euphrates valley, the area often referred to as Southern Mesopotamia. Those early urban centers, part of the Uruk culture, established colonies that led to the civilization of the north, as the people sought raw materials such as wood, stone, and metals which are absent in southern Mesopotamia.

Work at Hamoukar, first undertaken by McGuire Gibson, Professor at the Oriental Institute, between 1999 and 2001 showed that some of the elements associated with civilization developed there independently of influences in the south. The latest work suggests that the two forces may have had a violent confrontation at Hamoukar.

"It is likely that the southerners played a role in the destruction of this city," Reichel said. "Dug into the destruction debris that covered the buildings excavated this season were numerous large pits that contained vast amount of southern Uruk pottery from the south. The picture is compelling. If the Uruk people weren't the ones firing the sling bullets they certainly benefited from it. They took over this place right after its destruction."

Ironically, for archaeological work, ancient warfare has its advantages, especially when the besieged people may have been surprised. "Whatever was in these buildings was buried in them, literally waiting to be retrieved by us." In addition to many objects of value that are left behind, buried under massive amounts of debris, such "frozen contexts" are vital for functional analyses, helping to identify architectural units as domestic units, cooking facilities, production sites or buildings of administrative or religious use.

The mid-fourth millennium B.C. settlement at Hamoukar has many distinctively urban features. The area excavated so far contains two large building complexes built around square courtyards. Though both buildings follow closely a house plan known from other sites in Syria and Iraq, their function seems to have been non-domestic.

One of the structures contained a large kitchen with a series of large grinding stones embedded in clay benches and a baking oven large enough to fill a whole room, suggesting that food production occurred here beyond the needs of a single household. Each complex also contained a tripartite building (a unit consisting of a long central room surrounded by smaller rooms).

Objects retrieved from one of them, excavated in 2001, included stamp seals and clay sealings (lumps of clay used to close containers, usually impressed with a seal), suggesting that it was used as a storage and redistribution center for commodities. More stamp seals and over 100 clay sealings were found in 2005, including some sealings with incised drawings instead of seal impressions indicating that similar activities occurred in the second complex. The new data lends further proof to the theory, suggested first after the 1999-2001 excavations, that a city existed at Hamoukar during mid-fourth millennium B.C.

Work this season reinforced that certain elements of technological specialization were already present at Hamoukar several hundred years earlier than the time of the settlement's destruction.

This season three trenches were excavated in the southern area of the site where previous survey work had shown the presence of countless pieces of obsidian, both blades and production debris dating to the mid-to-late fifth millennium B.C., spread over an area of 700 800 acres.

"Finding production debris is actually as important, if not more important, than finding actual stone tools," explained Salam al-Quntar, pointing out a well-preserved obsidian core from which long, narrow blades had been flaked off in a radial pattern. "A settlement of 700 or more acres cannot have existed in the fifth millennium B.C.," al-Quntar says, "so we are assuming that this is a smaller 'shifting' settlement, which over centuries 'moved' across the area of the site. Little architecture has been found so far, but the remains of a storage room, which contained numerous large storage vessels, were identified, and numerous clay 'eye idols' assumed to be connected with cultic activities."

The nature of the contact that Hamoukar entertained with the south at that time remains to be investigated more fully. Reichel points out certain similarities that the architecture of Hamoukar shows with buildings in southern Mesopotamia, notably in the layout of the tripartite buildings. Some seal designs also show scenes resembling motives found in southern Mesopotamia and southwestern Iran. The pottery and almost all the other artifacts from the excavated area, however, were entirely of local character, betraying no southern influence. "We assume that some trade relations existed with the Uruk culture, but there is no evidence of Uruk control or domination over Hamoukar before the destruction," he said. But the southern Uruk clearly dominates the layers just above the destruction.

The 2005 season was the fourth season of archaeological work at Hamoukar. Between 1999 and 2001 three seasons were conducted under the co-directorship of McGuire Gibson. Following a four year hiatus and the 2003 Iraq War, in a political climate now overshadowed by misgivings between the U.S. and Syria, the resumption of a joint Syrian-American archaeological venture at this time on a site located so close to the border with Iraq may seem surprising.

Little if any problems could be reported, however, said Reichel, who praised the cooperation of Syrian government officials who issued excavation permit swiftly and offered logistical support. "They welcomed us like old friends."

Abdal-Razzaq Moaz, Deputy Minister of Cuture, in charge of Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, Syria, said, "Excavations at Hamoukar have played an important role in redefining scholar's understanding of the rise and development of civilization in the world. The resumption of a joint Syrian-American archaeological venture at this time shows the Syrians are interested to have such collaboration in the field of archaeology which allowed to have cultural exchange and mutual understanding between the two people, and to share a world heritage which belong to all the humanity." Besides the University of Chicago, Princeton, and the University of Pennsylvania and other universities have teams doing archaeological work in Syria, he said.

Contact: William Harms

w-harms@uchicago.edu

773-702-8356

University of Chicago

Fuente: Eurek Alert.org, 16 de diciembre de 2005

Enlace: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/

2005-12/uoc-eef121405.php

1 comentario

david segura -